TPG and Brookfield haul in $12bn for climate funds

This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Wednesday and Friday.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Greetings from steamy New York where it seems as if every shop and restaurant has a “Help Wanted!” sign, as staff shortages emerge as lockdowns end — giving workers new leveraging power. This is particularly stark in retailing: more than 200,000 retail employees quit or voluntarily left their jobs this past spring, according to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, although this outflow slowed recently.

Now, however, some companies are using ESG to fight back. Take Tapestry, the group that owns Coach, Stuart Weitzman and Kate Spade: it is announcing today an increase in hourly pay for “associates” (aka storefront workers) to at least $15, and bonuses for store managers to improve the “social fabric”. It also unveiled new ESG initiatives such as tying executive pay to diversity targets, introducing 100 per cent renewable electricity by 2025 and improving working conditions in the supply chain.

“We have accelerated our broader commitment to our stakeholders,” said Joanne Crevoiserat, chief executive officer. “The values of consumers have changed and so have the expectations of our associates.”

Is this a permanent shift in mindset? That remains unclear. Gen Z readers may scoff at Tapestry’s attempt to appear less “cheugy”. But if you want another sign of this zeitgeist shift take a look at this week’s news about two big fundraising initiatives for sustainability, as well as signs of swelling scrutiny of ESG ratings and university investment pools. — Gillian Tett and Kristen Talman

Private equity big shots blast into climate investing

In yet another sign that sustainability is serious business, Brookfield and TPG, two of the world’s largest private equity investors, both announced this week they have raised billions of dollars for their new climate-focused funds.

TPG said it had brought in commitments worth $5.4bn for its first Rise Climate Fund, and Brookfield said it raised even more, $7bn, for its Global Transition Fund.

TPG’s fund is being led by former Goldman Sachs chief and US Treasury secretary Hank Paulson (who we interviewed in depth on this topic back in January) and TPG executive chair Jim Coulter.

Brookfield’s new fund is led by former Bank of England governor, Mark Carney, and Connor Teskey, chief executive of Brookfield Renewable Partners.

TPG’s fund is part of its “Rise”-branded impact investment division, but unlike many other impact investments, a key selling point for the fund is that it is not giving up anything on returns. Brookfield, too, is seeking market rate returns.

If private equity managers can successfully deliver attractive profits and remove carbon from the atmosphere, Paulson believes it will open the floodgates for even more climate-centric investing.

“There will be a lot more capital coming in. You know, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and we want there to be a lot of imitation,” he told Moral Money.

It is also noteworthy that more than $1bn of the total raised by TPG came from other corporations, many of which have publicly committed to cutting their emissions. The private equity manager has teamed up with more than 20 companies including Apple, Alphabet, Bank of America, General Electric and General Motors to form a “Rise Climate Coalition” that will “unlock technologies, scale solutions, and deliver broad impact,” Paulson said.

For its part, TPG said it was “actively reducing our investments in the fossil fuel sector. Today, it is a very small part of our portfolio — representing about 0.5 per cent of our AUM — and we are rapidly decreasing that to zero”.

Brookfield too, sees an opportunity arising from the thousands of companies making net-zero pledges. Its fund “targets investment opportunities relating to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption, as well as increasing low-carbon energy capacity”.

“In terms of energy infrastructure investment, the amount [of money needed to decarbonise the economy] scales by another $1tn or $2.5tn, additional per annum by the middle of this decade and latter parts of the decade. So the opportunity set is huge,” Carney said. (Billy Nauman)

ESG data and ratings: who is paying for this?

One of the big fights that broke out after the 2008 financial crisis involved who should pay for credit ratings.

The credit ratings business started as a “subscriber-pays” model. But after the rise of copy machines in the 1970s, when free-riders could get reports without paying, credit raters started charging the companies to score their bonds. The payment change paved the way for S&P and Moody’s to give mortgage-backed securities and other products optimistic scores until the house of cards collapsed. (Check out Alice Rivlin’s terrific analysis of credit raters).

Now, the concerns about the payment model are coming for ESG raters and data providers. The International Organization of Securities Commissions (Iosco) on Monday published a request for comment on ESG ratings and data providers.

For now, at least 85 per cent of the ESG ratings market uses the subscriber-pays model — meaning that asset managers pay up for these scores. But the pay structure could change, especially if new regulations make ESG ratings essential for companies.

Still, Iosco said there were concerns about the current ESG ratings landscape. ESG raters can offer consulting services that advise companies on how to improve their ESG ratings or data products.

“This could result in conflicts of interest,” Iosco said, because the consulting side of business may provide information to the company to allow the firm to score better ratings.

The Iosco report fuels concerns about ESG data and ratings just as regulators are increasingly scrutinising the sector. The European Securities and Markets Authority has called for ESG ratings regulations. Hester Peirce, the top Republican commissioner at the Securities and Exchange Commission, has also raised concerns with ESG ratings.

Any future regulatory action could pose risks for MSCI, Morningstar, Bloomberg, FactSet and the other companies cashing in on the boom in ESG investing. (Patrick Temple-West)

Oxford students uncover undisclosed gifts from fossil fuel companies

Last year, Oxford university announced its endowment would sell its remaining holdings of fossil fuel companies. By the end of 2020, the £5bn endowment reported just 0.37 per cent of indirect investments in fossil fuels.

Yet, despite the divestment, Oxford retains cozy relationships with oil and gas companies — ties that are not publicly known, according to an environmental student group. From freedom of information requests, the Oxford Climate Justice Campaign obtained documents that show since 2015 ExxonMobil has given Oxford £6.9m — more than any other fossil fuel company has given the university during that time, the OCJC said.

In addition to Exxon’s contributions, Oxford has taken at least £18.8m from fossil fuel companies in the past six years. These contributions included £4.4m for antimalarial resistance at Oxford university’s Centre for Clinical Vaccinology and Tropical Medicine. Other donations include £231,869 to the Saïd Business School.

Exxon discloses some specific contributions doled out worldwide from its foundation and parent corporation. For 2020, Exxon gave $41m to higher education. Oxford is not listed. But in 2018, Exxon disclosed it gave $25,000 to the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

The students also found that Schlumberger, the world’s largest oilfield services company, gave the university an unknown amount of money. Oxford said it would not disclose the dollar amount because “these details would be likely to prejudice [Schlumberger’s] commercial interests”.

Oxford said in a statement that it safeguards its teaching and research programmes regardless of the source of the money. These funds “have no influence” on research or its conclusions. “None of the philanthropic funding highlighted by OCJC has gone into extraction and exploration research,” the university said.

The goal of disclosing these contributions, said Will O’Sullivan, a masters student studying environmental science, “is that this will make people more aware of the extent of fossil fuel funding the university receives”. (Patrick Temple-West)

Tips from Tamami

Nikkei’s Tamami Shimizuishi helps you stay up to date on stories you may have missed from the eastern hemisphere.

Following the G20’s endorsement of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, the Japanese government is moving to mandate climate risk disclosure.

Japan’s Financial Service Agency will launch a special committee to set the details of the rule this summer, Nikkei reported. If the process succeeds, more than 4,000 companies in Japan will be required to disclose climate risk on their securities report as early as the fiscal year ending March 2022.

Hong Kong, the UK, New Zealand, and Switzerland have already said they will require TCFD disclosures.

Japan already has more TCFD supporters — 428 companies and organisations in total — than the UK (365) and the US (314). More than 60 per cent of TCFD’s supporters in Japan are non-financial companies, compared to the UK, where just 30 per cent of supporters are non-financial companies. As many large corporations in Japan are already familiar with the guidelines, few expect a backlash against making TCFD disclosure mandatory.

“Not only big corporations, but also midsize companies, will start disclosing climate risks, if the disclosure becomes mandatory,” Kunio Ito, a professor emeritus at Hitotsubashi University and a chair of TCFD Consortium in Japan, said.

Chart of the day

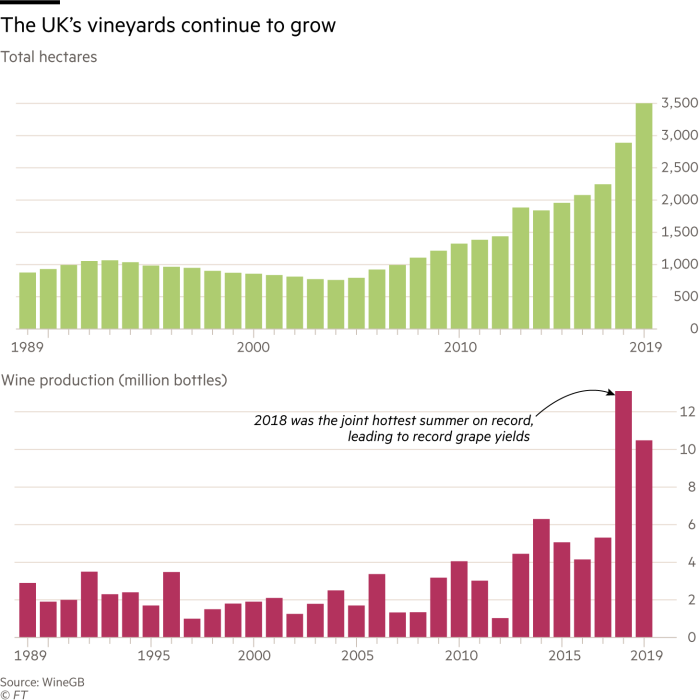

Climate change is shifting the frontiers of where food is grown as farmers and agricultural businesses adapt to warmer temperatures around the world. For wine grapes, those frontiers have shifted north both in Europe and North America. Canada, for example, has made big strides as a Pinot Noir producer, say wine connoisseurs. The UK, along with countries such as Denmark, is now part of the northern wine frontier in Europe. Please read our colleague Emiko Terazono’s article in the new FT special report on sustainable food and agriculture.

Smart read

Our colleague Dave Lee travelled to Paradise, California, to report on the livelihoods of people who survived the state’s deadliest forest fire in 2018.

Recommended reading

-

LGIM denies “greenwashing” over ESG China bond ETF (FT)

-

Rio Tinto probed by UK financial watchdog over disclosures (FT)

-

San Francisco Pension CIO Quits for Role with Clean Energy Firm (FundFire)

-

Boom in ESG Finance Creates One of Asia’s Hottest Job Markets (Bloomberg)

-

New Benchmarks Put an End to ‘Anything Goes’ for ESG Indexes (Bloomberg)

-

EU regulators clear €30.5bn French renewable energy scheme (Reuters)