Why the IEA is ‘calling time’ on the fossil fuel industry

Earlier this year a full-page colour ad appeared in the press: “Who is Fatih Birol playing for?” it asked, picturing the head of the International Energy Agency dressed in football garb.

The advert, placed by climate pressure group Avaaz, highlighted the awkward position of the IEA, a group founded to protect the interests of oil-consuming countries, as it starts to plan for a world without fossil fuels.

But this week marked a turning point for the world’s most influential energy body as the IEA published a bombshell report on how to reach net zero emissions by 2050 — a move that followed years of campaigning from investors, climate activists and even its own member countries.

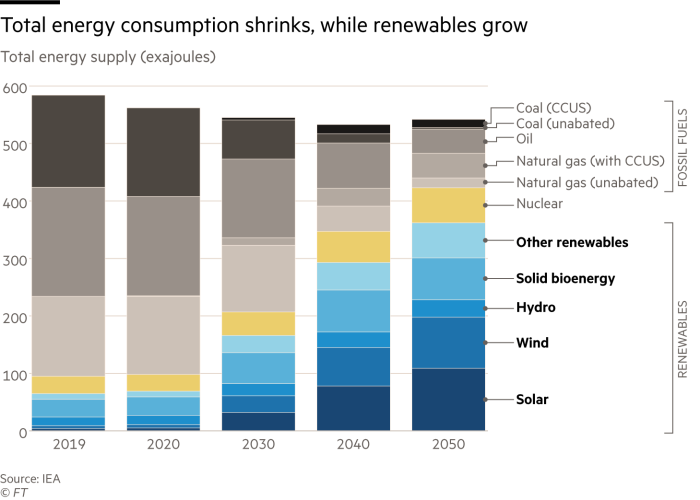

The Paris-based IEA is calling for a stop to new oil, gas and coal exploration but also for an end to the dominance of hydrocarbons. Energy investment needs to rise to $5tn annually by 2030, mostly on clean energy, up from $2tn today, it said.

“Effectively they are calling time on the fossil fuel era,” said Mark Lewis, chief sustainability strategist at BNP Paribas Asset Management. “It is like the pub landlord ringing the bell for last orders.”

It is a drastic turnround since the days of the Arab oil embargo and the group’s formation in the early 1970s. Its mandate has been to ensure enough oil is on hand in case of supply disruptions such as the first Gulf war, after Hurricane Katrina and during the 2011 Libyan crisis.

But just as global governments and corporations are under pressure to tackle climate change, the IEA, too, has had to overhaul itself.

“They’ve had to change because of the speed at which policymakers have decided to do something about global warming and because of the rapidly declining costs of renewable energy,” said Kingsmill Bond at Carbon Tracker. “They have had to reinvent themselves.”

What the IEA says matters. Its forecasts are used by oil companies to shape investment strategies, by governments to create energy policies and by stock market investors who want to understand the future.

Under Birol, the 63-year-old head of the IEA, the body has promoted energy security beyond oil, to gas and power, expanded its relationships with emerging market countries, and promoted energy efficiency and lower carbon technologies.

Yet it has struggled to fend off criticism that it was too fossil fuel-friendly.

Birol himself used to work at the oil cartel Opec — a sign of the revolving door between oil and gas companies and the IEA.

“The industry has used IEA scenarios as a shield to justify its continued investment in oil and gas,” said Andrew Logan, senior director of oil and gas at Ceres, a non-profit organisation. “This switch is quite momentous.”

The IEA fiercely denies it is beholden to or speaks for the oil and gas industry, stating that its mandate is energy security and, since 2015, to help governments transition towards cleaner fuels.

Factions have emerged within the organisation championing cleaner energy and lower-carbon technologies. Investors, climate scientists, environmentalists and governments have also lobbied the group heavily.

Bruce Duguid, at investment group Hermes Investment Management, said: “We went to Paris and met with Fatih in 2019 and made the case that this [a net zero road map] would be useful to investors, as well as the world.”

A public letter in 2019 asked the IEA to develop a net zero scenario — and immediately got the leadership’s attention. A handful of IEA member countries, including the Netherlands, Germany and Canada, then made similar requests.

“The discussion started to get louder and louder over the past two years, but that coincided with political realignments — with the UK, EU, US and others adopting net zero targets,” said Rachel Kyte, dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University and former UN clean energy envoy. “The logical consequences of hitting those targets is what you see in this report for the first time.”

The Biden administration in the US has only reinforced the need to change.

“The definition of energy security is changing,” Birol told the Financial Times after the report’s publication. “We do not have an objective to please anybody.”

For the IEA, this has meant a steady shift in messaging. It went from warning about supply shortfalls and higher investment needs to saying that despite the Paris climate agreement, the status quo would remain. “Fossil fuels, in particular natural gas and oil, will continue to be a bedrock of the global energy system for many decades to come,” the IEA said in 2016.

Now, it is not only calling for the end of oil and gas’s prominence, its report says “the world has a viable pathway”.

In doing so, however, analysts say the group risks undermining its mission.

Oil prices are rising — crude rose to $70 a barrel on Tuesday, the highest in more than a year — and dramatic falls in investment in new production amid the coronavirus crisis mean the IEA is now priming the world for a supply shortage, says an investor.

One oil executive warned that the report would entrench the narratives of rival camps rather than engage in a meaningful and necessary dialogue about changing the world’s consumption patterns.

“Does the IEA really believe their scenario is achievable or are they just demonstrating the sheer impracticality of it?” said Gordon Ballard, an adviser to the oil and gas industry.

Another investor, who pushed for the net zero report and did not want to be seen criticising it, said: “They show their conclusions in detail but not enough on their calculations for getting there.”

One outcome could be business as usual. Listed oil companies are not obligated to take further action and major producer nations are still ramping up production capacity and market share.

Neil Atkinson, former head of the oil markets division at the IEA from 2016 until January this year, said: “For people outside the agency it looks like they’ve suddenly got religion, but that is categorically not the case — they’ve been building up to a road map like this for some time.”

Follow @ftclimate on Instagram

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here