Why rushing to document war crimes in Ukraine poses problems

This article is an on-site version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morningGood morning and welcome to Europe Express.

The fact that Ukrainian courts have already started issuing convictions for war crimes and many more prosecutions are already under way, little over three months since the war started, has surprised many. But there are also drawbacks to the flurry of experts and human rights groups seeking to collect evidence for a trial that would eventually hold the Russian leadership accountable for those crimes.

With the European Central Bank meeting in Amsterdam on Thursday, the bulk of its 25 governing council members are expected to support a proposal to create a new bond-buying programme if needed to counter borrowing costs for member states such as Italy spiralling out of control.

And as the microchip shortages continue to cause havoc for Europe’s industries, we’ll hear from a senior US official who recently visited factories in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Drinking from a fire hydrant

Gathering forensic evidence from mass graves, interviewing survivors and witnesses who have filmed or taken audio notes with their phones — these are all pieces of evidence that could eventually be used to prosecute the Russian leadership for war crimes. But the fragmented landscape and lack of overview could pose problems for future prosecutions, writes Valentina Pop in The Hague.

Bringing high-ranking officials to justice takes several years and in the meantime, the evidence has to be stored securely, catalogued so it’s easily accessible by the prosecution and also made available to the defence when the case goes to trial.

That task will be even more complex as it is yet unclear whether the existing International Criminal Court in The Hague, which has the power to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity, including genocide, or a dedicated special tribunal for Ukraine will be constituted to handle those cases.

Neither Russia nor Ukraine are participating in the ICC, but Kyiv has asked The Hague-based court, through its European allies who are members, to open an investigation on its territory, which is already under way since the first week of the war.

ICC prosecutor Karim Khan says that the main task at hand for now is to co-ordinate evidence gathering efforts and for governments to allocate more resources to sift through the “deluge” of information being collected.

“These are massive data sets — social media, phone, video, statement, every type of evidence you can think of. One of the challenges is how do you deal with that, in order to avoid drinking from a fire hydrant,” Khan told a group of reporters last week. One solution would be to deploy artificial intelligence and store the evidence securely in the cloud, provided ICC member states fund such partnerships with tech companies.

The other issue, he said, was in avoiding what happened in the case of the Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, where there was “over-documentation, a stampede towards collection” and where victims were traumatised by being interviewed over and over again by multiple actors.

In a bid to pre-empt that, Khan’s office has for the first time joined a coordinating team put together by the EU’s judicial co-operation agency Eurojust and is regularly in touch with the United Nations’ human rights commissioner, who is also carrying out her own inquiry in Ukraine, “to try to make sure we deconflict and we don’t over-document ourselves”.

In addition to the UN, EU countries and the ICC, the UK last month also deployed war experts to assist the Ukrainian government with evidence-gathering. Another international body, the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (which counts both Russia and Ukraine among its members) is also investigating alleged war crimes in Ukraine.

All the international teams, human rights groups, NGOs and Ukrainian officials interviewing victims raise also the issue of evidence collecting standards, says Iva Vukušić, an assistant professor in international history at Utrecht University. “It’s clear that not everyone on the ground is trained in the specifics of what is considered admissible evidence.”

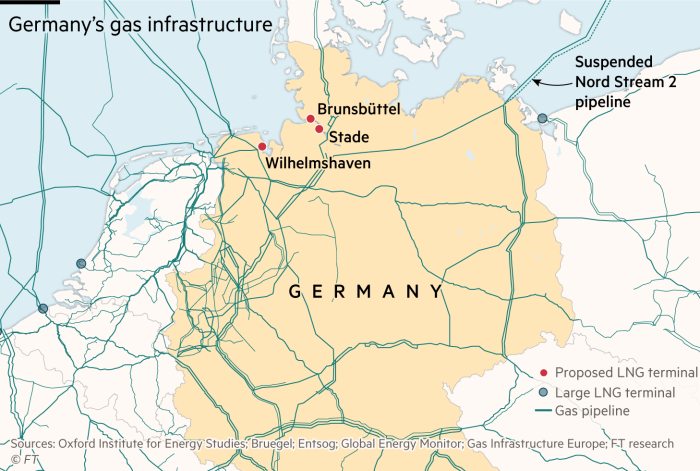

Chart du jour: Gas transformation

Germany’s recent policy shift away from Russian pipeline gas, but still banking on liquefied natural gas shipments and the rapid construction of LNG terminals could clash with the country’s commitment to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2045.

Chips and friends

ASML of the Netherlands, which makes the machines that make semiconductors, has become somewhat of a tourist attraction for politicians, writes Andy Bounds in Brussels.

The plant on the outskirts of Eindhoven hosted Don Graves, the US deputy secretary of commerce, last week, when ASML announced it will invest $200mn in its plant in Connecticut. A few months ago Ursula von der Leyen, commission president, and commissioners Margrethe Vestager and Thierry Breton, made the same trip.

Graves also followed Breton to Imec in Leuven, Belgium, which is pioneering chip production research.

After the visit, Graves told Europe Express that the Dutch factory was an example of “friendshoring”, investing in allied countries. Still, ASML has four facilities in China too.

A global shortage of semiconductors has reduced the production of everything from cars to refrigerators — and supply chains have been further strained by China’s strict Covid-19 lockdowns in recent months.

Graves said he wanted to ensure “that the US, the EU and our partners around the globe have an adequate supply of microchips for all of our companies and the products that our consumers need”.

He also stressed that the vast sums of money governments are giving companies to invest should not create “direct competition” between like-minded countries. It would be a waste of our time and money for us to try to invest in ways that are not complementary,” he said. However, with both the US and EU investing around $50bn and stressing the sovereign need to make even low value chips, that might be hard to do.

As a new blog from Brussels think-tank Bruegel points out: “Estimates of support provided to the industry by the US, China, Japan, South Korea and the EU amount to $721bn, or 0.9% of 2020 global GDP. This is bound to create major competition distortions.”

It is also likely to lead to overcapacity in a few years’ time.

On one area Graves spoke about there is harmony: export controls on sensitive goods to Russia. He said there were signs they were having an effect, although the claims are hard to verify.

“Reports suggest that Russian tank production has essentially stopped. We’re hearing that their aerospace industry is significantly hamstrung, that they aren’t able to get the replacement parts and components that they need and that their laboratories are, in many cases, shutting down. And their scientists, their experts are leaving the country because they no longer have the ability to work.”

What to watch today

-

European parliament holds its plenary session in Strasbourg

-

EU commission vice-president Margaritis Schinas meets UN secretary-general António Guterres in New York

. . . and later this week

-

European Central Bank governing council takes place in Amsterdam on Thursday

-

Justice, home affairs and competitiveness ministers meet separately in Luxembourg Thursday and Friday

-

First round of French parliamentary elections on Sunday

Notable, Quotable

-

“Humiliating” Vladimir Putin: Ukraine has hit back at Macron’s warning against embarrassing the Russian leader as Kyiv suffered first Russian missile attacks since April apparently aimed at railway infrastructure.

-

No horizon: The British government is set to walk away from the EU’s multibillion scientific research programme known as Horizon, as it prepares to rip up the Northern Ireland protocol.

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: europe.express@ft.com. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe