Tree-tracking start-ups surge as climate pledges take root

Tree-tracking technology is drawing investor attention as the boom in planting pledges to combat climate change highlights a basic problem: how to identify new growth and how healthy it remains.

Remote tracking tools using a combination of artificial intelligence, drones and satellite imagery are attempting to monitor vast swaths of land to map forests and calculate the volumes of carbon they are absorbing. Forest-monitoring start-ups raised at least $44m in early stage funding this year.

“Nobody has a database about all the [forest] restoration,” said Fred Stolle, deputy director of World Resources Institute’s Forests Program. “Different groups are trying to gather data . . . At the moment it’s very fragmented.”

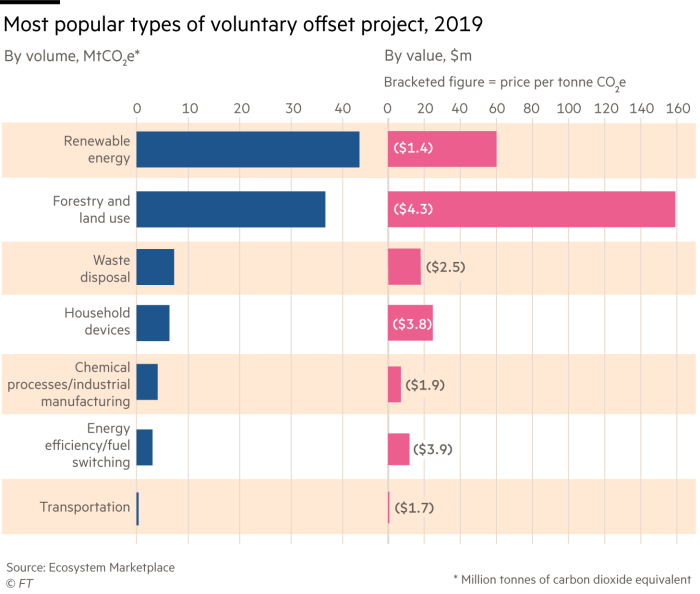

The chase for the data comes as companies are increasingly prepared to pay to monitor the forests that generate carbon offsets — which organisations can use to compensate for emissions.

Governments seeking more accurate estimates of national tree coverage, as they set their own emissions targets, are also looking for accurate readings.

The proliferation of tree planting pledges to support net zero plans has sparked a market for forest-related products and technologies. Barclays last year estimated the opportunity for “investment in nature” at $3.6tn.

Morgan Stanley said in April that remote forest monitoring systems could lend more credibility to the expanding carbon offsets industry.

Mapping the growth of new trees is “much more difficult” than tracking deforestation, which researchers have been doing for years, said Shaun Quegan, lead scientist of the European Space Agency’s biomass mission.

New woodland might not be detected by satellites for several years, or might be confused with the growth of shrubs or other plants, he said.

Traditional in-person monitoring of tree growth generates detailed information but is labour intensive, expensive and can be impractical for large or remote projects. As a result, not all countries have accurate estimates of forest cover.

The European Space Agency is developing a series of maps of the world’s above-ground vegetation, to monitor change over time and “support global and national policy aimed at meeting emission reduction commitments”.

Tools designed to monitor forests that generate carbon offsets are also in demand, to address concerns about the integrity of offsetting projects. Critics point to the difficulty of ensuring that new trees remain standing, and warn that conserving one area may push deforestation to an adjacent region.

Tree-tracking start-up Pachama matches the buyers and sellers of offsets, and recently raised $15m in a funding round led by Breakthrough Energy Ventures, the investment group founded by Bill Gates.

It says it can help buyers keep a “remote eye” on the woodland generating offsets by using artificial intelligence, combined with satellite and lidar, which uses a laser light pulse for measurement, to estimate forest cover and carbon absorption rates. Customers include Microsoft, Shopify and SoftBank.

Index Ventures — an early investor in food delivery group Deliveroo and online trading platform Robinhood — led a $7.8m funding round in May for Sylvera, an offset ratings provider that uses geospatial data, satellite imagery and machine learning to analyse forest offsetting schemes.

Also this year, Swedish forest data company Katam raised $1.2m, and NCX — which uses remote sensing to identify woodland that could generate offsets — raised $20m from investors including Microsoft’s Climate Innovation Fund and Salesforce founder Marc Benioff’s Time Ventures.

Gold Standard, which certifies offsetting schemes, told the FT it was testing whether several remote monitoring methods were accurate enough to provide “interim verifications” of offsetting projects. Scheme developers who want faster and cheaper approvals had been “clamouring for remote sensing”, the group said.

As tracking technology improves, it could become the “prevailing method” for monitoring and verification, Gold Standard added.

Other start-ups, including Treeconomy and Dendra, are developing systems to better estimate the volumes of carbon being absorbed by trees and plant seeds at scale using drones.

However, experts caution that remote sensing alone is likely to be insufficient, particularly for estimating carbon absorption.

Remote tools struggle to distinguish between tree species — an important factor in estimating the amount of carbon a tree has sequestered, says Thomas Pugh, a lecturer at Lund University’s department of physical geography and ecosystem science.

The systems also cannot accurately calculate the amount of carbon stored in the soil, which can vary widely. Those are “big limitations”, Pugh notes.

Checking remote measurements against those taken on the ground is crucial, he adds.

Dmitry Schepaschenko, a forestry researcher at Austria’s International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, said satellites and drones played a “more and more important role” in forest monitoring, but “people on the ground are also needed”.

Measuring a tree’s height and width was important for accurately estimating carbon absorption, and this was challenging to assess remotely, especially for dense, tropical forests, he said. “Not everything can be seen through the canopy.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here