SoftBank to slow investments following crash in tech holdings

SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son has told his top executives to slow down investments, as the world’s largest tech investor seeks to raise cash amid falling tech stocks and a regulatory crackdown in China.

The Japanese billionaire made the remarks to his leadership team at a recent meeting, according to people briefed on the discussions, as the group responds to the massive hit to the value of its holdings in recent months.

The previously unreported discussions offer a rare glimpse into the growing tension within SoftBank, which has disrupted the tech investing landscape since launching its first Vision Fund in 2017.

Rising interest rates and the war in Ukraine have ravaged its holdings and the plummeting value of its China investments served as a stark reminder of how Son’s personal fortunes have become entwined with the company he founded — and its $100bn fund beholden to the global appetite for tech risk.

The estimated writedown at the Japanese group for this quarter stood at $30bn, although a recent uptick in some shares meant it was now closer to around $20bn, the people said.

“Valuations for Chinese companies listed overseas have collapsed,” said one person close to SoftBank’s China team. “We don’t expect a turnround anytime soon.”

One person familiar with the company’s plans added that SoftBank is pushing to raise cash and is evaluating assets that could be liquidated.

During the sell-off, Son became alarmed over his personal borrowings against SoftBank shares, people close to him said.

SoftBank declined to comment.

Some analysts believe SoftBank should be able to weather the storm, pointing to an estimated $23bn cash on hand held by the group. That, according to New Street Research, is enough to “cover interest, bond redemptions, and a potential $6bn Alibaba margin call” and continue the share buyback programme and fresh investments, although at a slower pace. SoftBank’s financial policy also includes having a cash position covering bond redemptions for at least the next two years.

The Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi-backed Vision Fund was originally intended to be the first in a string of funds run by SoftBank’s investment arm. Its image was severely dented by its freewheeling culture and after some of its high-profile bets, including one on office-sharing group WeWork, imploded. For its second Vision Fund, SoftBank failed to raise outside money.

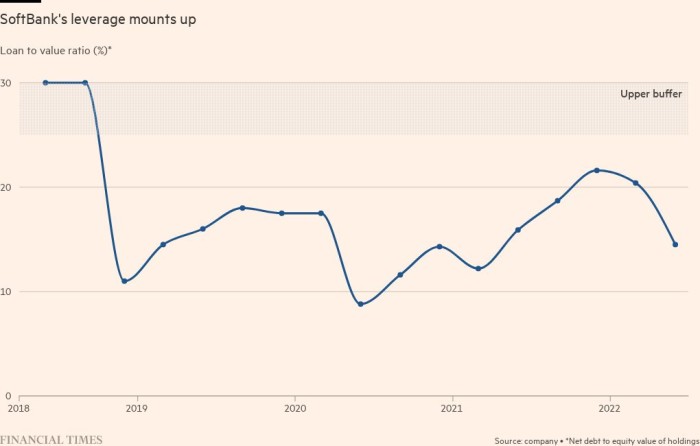

SoftBank’s shares have fallen more than 40 per cent in the last year. A metric showing its net debt compared to the value of its holdings — closely monitored by Son as a gauge of the company’s financial health — has jumped from under 10 per cent in mid-2020 to 22 per cent, creeping close to the 25 per cent threshold Son has vowed not to cross in “normal times”.

The reckoning at SoftBank has sent shockwaves through capital markets as traders watch for signs of trouble in the Japanese company’s vast portfolio.

Early in March, SoftBank tapped Goldman Sachs to market a $1bn block of shares in the South Korean ecommerce company Coupang, one of the largest wins from the first Vision Fund.

SoftBank sold the stake at under $21 per share, a 40 per cent reduction from the price of Coupang’s blockbuster initial public offering last year, which had valued the Japanese company’s stake at roughly $20bn.

In a bid to raise cash, SoftBank has also used stock in Coupang and other large holdings in the Vision Fund as collateral for loans. The Japanese tech group is also finalising loans worth as much as $10bn tied to the IPO of UK chip designer Arm Holdings, following the collapse of its $66bn sale to US rival Nvidia last month.

“If you look at all the action, it’s very clear that they are in desperate need of capital,” said Amir Anvarzadeh, a strategist for Japan equity at Asymmetric Advisors who has recommended shorting SoftBank.

Son has also taken out personal loans against his own stake in SoftBank, recently raising the collateral to about a third of his total holdings in the group.

One of the people with knowledge of the situation said Son was “very concerned” about the rising collateral. Son owns about a third of SoftBank and has borrowed against his stake to personally invest in Vision Fund.

A large chunk of SoftBank’s net asset value is in the US and China, where authorities have launched efforts to tackle the market power of big tech companies. The value of SoftBank’s Alibaba stake plummeted from about $208bn in November 2020 to $69bn in March after Chinese authorities called off the blockbuster IPO of its fintech arm Ant Group and moved to rein in the tech sector.

“When Alibaba collapsed a week or two ago, it worried me because the margin of safety has shrunk and the argument for SoftBank shares has become less convincing,” said one Asia-based investor betting on SoftBank’s long-term growth.

The billions put into Chinese tech groups by the Vision Fund face steep losses. Nearly all of its listed Chinese investments are trading below their purchase prices and the billions it put into online education firms are in jeopardy after Beijing banned profitmaking in the sector.

The fund’s single largest China bet on ride-hailing giant Didi is about $9bn underwater, with its apps deleted from local mobile-app stores as part of a national security investigation into the company.

The slowdown follows a year of furious dealmaking. SoftBank made investments in 195 private companies last year, making it one of the busiest tech investors during a record period for venture investment, according to CB Insights data.

Executives at SoftBank’s second Vision Fund, which manages $40bn of the company’s own capital, have recently tried to convince peers of its prudence.

Speaking at a Los Angeles venture capital conference in March, Vision Fund managing partner Nagraj Kashyap said the fund aimed to make fewer investments, but with higher amounts of conviction.

“There is a slow reset of expectations that is trickling through the private markets,” Kashyap said. “They have not caught up to the public markets, clearly.”