Is Big Tech flabby?

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Earnings season starts in earnest today, with big companies from Johnson & Johnson to Union Pacific reporting. We don’t expect many big surprises, other than perhaps some cautious guidance. The real pain in growth and margins, if it comes, will be in the second half. Let us know what you expect: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Big Tech, job cuts and activists

Elliott Management, the activist investor, has taken a stake in Salesforce, and plans on “working constructively with Salesforce to realise the value befitting a company of its stature”. Salesforce is not alone among big-cap techs. Activists have also banged on the doors of Meta and Alphabet in recent months.

It would be surprising if this trend did not continue. Activists like companies that have (1) strong underlying profitability, (2) structural issues that dilute, obscure or misdirect those underlying profits and (3) a weak bargaining position.

Points one and three are easy. Big Tech got big because of high profitability, or at any rate high growth suggesting the possibility of high profitability. Meanwhile, the absolute rout in Big Tech stocks has created vulnerability to investor demands. Point number two is trickier, but many Big Tech companies spent a lot of money in order to keep growth going in the past few years. The activists can tell them to stop, which should give profits a bump. This is what investors have in fact asked of Meta and Alphabet. I’d be surprised if this was not Elliott’s basic line on Salesforce, too.

(Activists in Big Tech have not always focused on costs, by the way; in earlier cycles, the demands have run from “buy back lots of shares” to “fire Steve Ballmer”.)

It is not too surprising then, that Google, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft and Salesforce have all announced job cuts. The companies’ statements about the cuts have all said the same thing: demand was high during the coronavirus pandemic, we hired loads of people, but now things have slowed. The story makes broad sense, but the unanimity of the message and near simultaneity with which is was transmitted makes me suspicious about whether it (how to put this nicely?) obscures a more complex situation.

There are lots of big questions to answer. Are the activists right that Big Tech has let itself go, in terms of capital allocation? Is it more true of some of the companies than others? Are the companies right that the extra weight is a pandemic phenomenon — or are the issues more fundamental?

Here is a table laying out some of the basic data:

One observation to make here is that these companies are diverse. For starters, Microsoft, Meta and Alphabet are much, much more profitable, both on a per employee and return on assets basis, than Amazon and Salesforce. Amazon is simply an asset-heavy, human-capital-heavy business. Salesforce still has the low profits of a growth-stage tech company, at least when profits are calculated on a GAAP basis (return on assets is calculated above by dividing profit after tax into total assets).

This point has implications for activists. Taking on Meta, an activist might say “just pull back on your metaverse investments and focus on your great core business”. With Salesforce, Elliott might have something to say about, say, acquisition strategy, but it is the main business itself that requires changes.

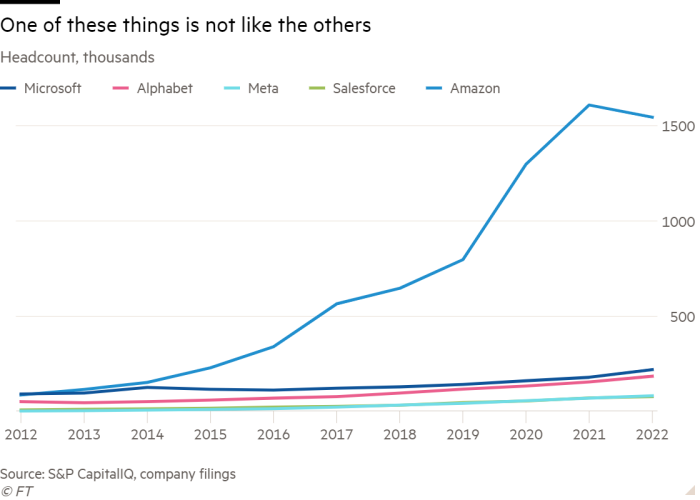

Will reversing the excesses of the pandemic, particularly in hiring, be enough to satisfy investors? Here is a chart of the companies’ headcount over the past decade (the 2022 number comes from the most recent available quarter):

What this chart shows is that the pace of hiring did not pick up that much during the pandemic. Microsoft did accelerate hiring by a bit, and Alphabet by a smidge, but at the other three, the trend has been consistent since at least 2017. The job cut announcements, then, are best understood as signalling seriousness about costs to restive investors. In and of themselves, they are minor tactical adjustments at best.

A 10,000 job cut is large — and huge for each of those 10,000 people — but remember that these companies that have been adding that many workers or more every year for years. This is not necessarily a meaningful change to business as usual.

You may have noticed that Amazon is not included in the chart. That is because when it is included, the chart looks like this:

Again, Amazon is a totally different animal. It’s hiring as it integrates distribution vertically and diversifies its business on a different scale from the rest of Big Tech. It really belongs in a different discussion.

How do we assess whether the rest of Big Tech’s decade-long hiring binge has made the companies inefficient? From the outside, it’s not that easy. Revenue per employee has been stable to up (except, again, at Amazon):

Looking at operating expenses as a percentage of revenues, the story is more uneven: multiyear improvements at Microsoft and Google, while Meta and Amazon have slipped. Again, the basic point is that the trends are long established. This is not about the pandemic.

There is much more work to be done here, but there is one key conclusion we can reach already. The pandemic hardly changed these companies at all; they don’t look very different from a few years ago. It also strikes me as unlikely that they have seen very significant changes in demand recently, given that the slowdown is only starting to show up in the data now.

What has changed, then, that has activists circling and the companies announcing austerity measures? The stock prices, of course. The rumblings we are seeing in Big Tech now have nothing to do with any decision the important companies have made in the past five years, and relatively little to do with recent financial performance of the companies (with the exception of Meta, which is in a proper crisis). Substantively, all that has happened is that the sell-off has changed the power dynamics between the companies and their investors.

You will notice that one of the Big Tech groups has not announced staff reductions, and has not attracted attention from activists since the sell-off began: Apple. That is no coincidence. Its shares are only off 20 per cent.

One good read

Aswath Damodaran on the current level of the equity risk premium and expected returns.