Inside Ukraine’s online defence: the battle against Moscow’s cyber attacks

As Russian troops massed on the border on January 14, dozens of Ukrainian government websites were defaced with the words “be afraid and wait for the worst”.

The co-ordinated hack was viewed by Ukrainian and western cyber security officials as an initial warning that Russia would wage a fearsome digital war alongside a ground invasion of the country. Soon after, a series of major cyber attacks were detected on energy and communications groups — but then just as quickly repelled.

A month into the Kremlin’s war, Ukrainian officials have taken solace that critical networks have withstood weeks of cyber assaults, but as one official warned, Russia’s vaster resources meant it could steadily wear down the online resistance. “Our networks are our people,” he said. “And Russia is killing our people.”

This account of the first phase of Russia’s cyber war on Ukraine is based on interviews with Ukrainian and western officials with direct knowledge of the events, many of which have not been previously reported.

Around the same time as Ukrainian government sites were defaced in January, Ukrenergo, the government-owned power transmission company, observed an uptick in attempts to break into its networks. Engineers at the company were already on high alert, tasked with preventing a repeat of a 2015 cyber attack that saw Russian hackers cut electricity to parts of Kyiv.

By February, the number of failed attempts was three times higher than a year earlier, said Oleksander Kharchenko, an adviser to the ministry of energy. One particularly audacious attempt involved a compromised local employee trying to sneak malicious code on to company premises.

“They were trying everything, trying to break in through our website, trying DDoS,” said Kharchenko, describing a distributed denial of service, where thousands of computers send simultaneous requests in order to bring down systems. “It was 24/7.”

Within an hour of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s pre-dawn announcement on February 24 that he had ordered troops into Ukraine, thousands of modems across central Europe lost their connection to a satellite flying 36,000km above earth.

As the modems that connected customers of the US-based ViaSat satellite flickered their warnings, the sudden loss of data cascaded through Europe. Some 5,800 wind turbines owned by Germany’s Enercon switched to back-up mode as the company lost its ability to remotely monitor their operation. Thousands of people in Italy, Germany and Poland lost their internet connections. Viasat has acknowledged a “cyber-event” but has not blamed Russia for it.

In Ukraine, that sudden loss of data connection hit its scattered army bases, according to two Ukrainian officials. But as dozens of military grade modems suddenly stopped working the troops quickly moved to other encrypted communications. “There are always back-up systems,” said one of the people with knowledge of the incident. “It was just as the war started, but the teams were trained for this situation, to avoid catastrophe at all costs.”

Ukrainian telecommunication networks and energy grids have largely remained resilient, with some, such as that in Mariupol, collapsing only after a rain of missiles and mortars had taken out physical infrastructure, said Victor Zhora, a senior official tasked with coordinating the country’s cyber defences with western allies.

The intensity of attacks, other than on the electricity networks, has fallen since the beginning of hostilities, he added. “We now have periods of more quiet than before, and that could be explained by the concentration of our adversary on conventional war on attacks against Ukrainian civilians instead of IT infrastructure.”

Ukrainian engineers, particularly those guarding civilian infrastructure from cyber attacks, have been able to call in support from western companies such as Cisco, Microsoft and Google, which is currently defending at least 150 Ukrainian firms.

Interspersed with these are occasional cyber assaults of ferocious intensity. On February 24, around the time the ViaSat satellite connections were severed, nationwide assaults were also being carried out by some 100 highly skilled hackers from nearly a dozen groups with ties to Russia and Belarus, said Serhii Demadiuk, the deputy secretary of the National Security and Defence Council, and former head of the Ukrainian cyber police.

“The cyber attacks on the IT infrastructure, which preceded the physical invasion and bombing of Ukrainian cities, are the most complex cyber operation in history and are one of the first examples of what a real cyber war looks like,” said Demadiuk.

In one instance, he said, a large Ukrainian security organisation with more than 5,000 employees and 1,000 servers averted a devastating loss of all data with only 90 minutes to spare because of warnings from a US partner.

Those attacks have yet to cease. A financial institution targeted on the first day of the war saw another spate of so-called wiper malware on March 14 attempting to erase all its data, said researchers at Symantec, alongside an attempt to wipe data at a major IT provider.

“The Ukrainians now have the expertise that maybe they didn’t have back in 2015,” said Matt Olney, who heads a threat intelligence group inside Cisco. “They’ve learned the lessons of the past five, six years.”

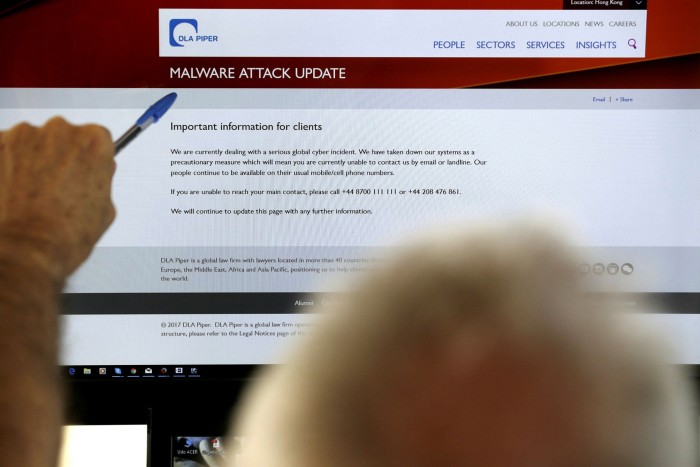

Olney helped study the original Russian attack in 2015 that took down parts of Ukraine’s energy grid, and a 2017 malware, nicknamed NotPetya, that effectively deleted large parts of computer systems. Cisco has about 500 people working to help customers respond to attacks.

“[The Ukrainians] built the processes, the boring things, the playbooks,” said Olney. “The things that are just obnoxious to do in peacetime. Now that we are in this critical situation, they’re all paying off.”

In one instance, the bombardment required engineers to physically cart servers to a different city and bring them back online — a laborious and complex task even during normal times — to keep systems running, he said.

Are you personally affected by the War in Ukraine? We want to hear from you

Are you from Ukraine? Do you have friends and family in or from Ukraine whose lives have been upended? Or perhaps you’re doing something to help those individuals, such as fundraising or housing people in your own homes. We want to hear from you. Tell us via a short survey.

US officials have suggested that part of Ukraine’s surprising resilience in the cyber battlefield is because Russia has not fully unleashed its potential for devastating assaults.

“Why haven’t we seen the real A-team?” US senator Mark Warner said at a conference last week. “I still am relatively amazed that they have not really launched the level of maliciousness that their cyber arsenal includes.”

Others, including Olney at Cisco, suggested that Russia was using its cyber arsenal for more traditional espionage, such as hacking western networks to stay ahead of sanctions, or monitor troop movements.

There is also growing concern that Moscow may yet lash out on a wider array of targets. Joe Biden, the US president, warned American businesses on Tuesday to strengthen their cyber-barricades in the expectation of Russian cyber attack.

“The magnitude of Russian cyber capacity is fairly consequential,” said Biden. “And it’s coming.”