Inside ‘Project Tinman’: Peloton’s plan to conceal rust in its exercise bikes

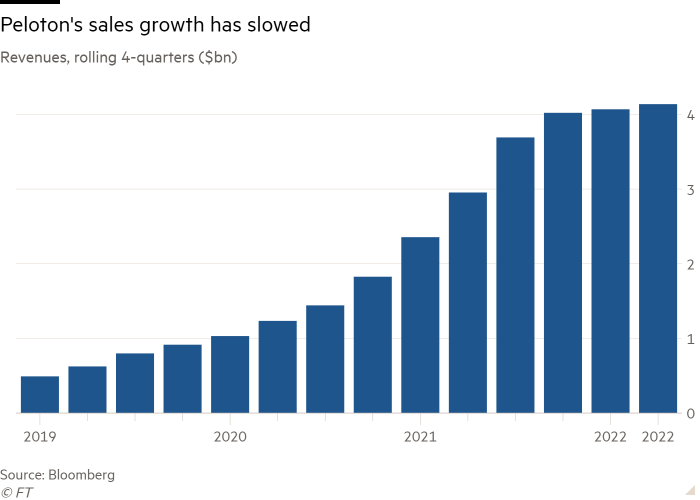

As Peloton’s stock price began to tumble last autumn and just months after a costly recall of the connected fitness company’s expensive treadmills, its executives were confronted with a new crisis.

In September last year, staff at Peloton warehouses, which receive high-end bikes originally manufactured in Taiwan, noticed that paint was flaking off some of the exercise machines.

The cause was a build-up of rust on “non-visible parts” of the bike — the inner frame of the seat and handlebars — and did not affect the product’s integrity, Peloton recently told the Financial Times.

Instead of returning the bikes to the manufacturer, executives hatched a plan, dubbed internally as “Project Tinman”, to conceal the corrosion and sent the machines to customers who had paid between $1,495 and $2,495 to purchase them.

The project was first revealed in FT Magazine last week but eight current and former Peloton employees across four US states have provided further details on the operation.

They described the plan as a nationwide effort to avoid yet another costly recall just months after the company’s most tragic episode — the death of a child due to the design of its treadmill.

Internal documents seen by the FT showed that Tinman’s “standard operating procedures” were for corrosion to be dealt with using a chemical solution called “rust converter”, which conceals corrosion by reacting “with the rust to form a black layer”. Employees said the scheme was called Tinman to avoid terms such as “rust” that executives decided were out of step with Peloton’s quality brand.

Insiders were also angered about enacting a plan that they argued cut across Peloton’s supposed focus on its users, who are called “members” to evoke a sense that buyers are more than customers and part of a broader community. Tinman also put a spotlight on the company’s quality control process versus meeting aggressive sales targets in the search for growth.

“It was the single driving factor in my beginning stages of hatred for the company that I had spent the previous year and a half falling in love with,” said an outbound team lead, who reviews products before they are shipped to customers.

Peloton said the issue affected at least 6,000 bikes and that 120 staff had undertaken “rigorous testing” on the devices to conclude the rust — which it described as “cosmetic oxidation” — had “no impact on a bike’s performance, quality, durability, reliability, or the overall member experience”. The company added it discovered the problem “as part of the pre-delivery inspection process of our products that we’ve had in place since 2016.”

The US Consumer Product Safety Commission, which oversaw the recall of Peloton’s treadmill, would not say whether it had been alerted to the corrosion issue, but said companies must notify it if they suspect defects “which could create a substantial product hazard or . . . an unreasonable risk of serious injury or death”.

The company is in turmoil, having announced 2,800 job losses this month, with co-founder John Foley stepping aside as chief executive. Peloton plans to cut $800mn from its annual costs.

That move came after 12 months in which the company’s shares had plummeted 80 per cent, wiping about $38bn off its market capitalisation. The company’s stock has rallied since, partly due to news that Nike, Amazon and other groups were evaluating potential bids and as activist investor Blackwells Capital pushes for a sale.

Four months before the first sighting of rust, Peloton had been pressured by the CPSC to recall 125,000 Tread+ products, each costing $4,300. The year before, the company issued a recall on 27,000 clip-in pedals, following reports of injury while cycling.

Two warehouse workers who handled bikes late last year claimed that many with “severe” rust were delivered to customers. One staffer sent the FT a photograph last week, suggesting rusted bikes were still arriving at one regional warehouse in the US.

Peloton said the issue was “cosmetic” and was resolved by sending the products to special locations for “rework” before they went to a “final mile” warehouse, where they would undergo another check-up before being delivered to customers.

An internal document read: “It is acceptable if you see some rust through the black layer as the severity of this rust is reduced using the rust converter.”

This directive alarmed some employees because Peloton had previously disqualified bikes with any rust from becoming a “refurb” — a discounted bike only available to employees and their friends — let alone sold at full price.

“Even for Bike-Pluses [products that cost $2,495] that were rusted internally, they were still delivering them,” a current employee said. “Sometimes bikes had stuff on the outside, so we couldn’t deliver them, but . . . [there were] a lot of bikes that were rusted on the inside that they still sold.”

Tinman procedures dictated that if the bikes failed to meet cosmetic standards, they were to be scrapped or turned into a “refurb”. But multiple warehouse workers have said these quality controls were often not followed in order to hit “unrealistic” sales quotas.

One current employee described their supervisor as “pissed” that they lacked enough specialists to take care of the issue. “We couldn’t keep sending them to our refurbish area. We just had to build them, to try to clear [the rust] off and send them out.”

Another worker said the secondary check would sort bikes into “sellable” and “non-sellable” categories. He added that when Peloton was experiencing low inventories amid a supply chain crisis that made it hard for the company to keep up with demand, some workers felt pressure to reclassify “medium rust” bikes to “light rust” then clear them for shipment.

“It was all very subjective,” this person said. “It was framed as a ‘it’s either this or no delivery’, which was a non-option from our management.”

Peloton said this was not company policy. “There was no direction by Peloton to reclassify or deem this inventory unsaleable and it is against Peloton’s policy and practices for Peloton to put in the market unsaleable inventory. If anyone did so, they were acting against the company’s policies and practices,” it said in a statement.

Rust is not covered under the warranty, according to the company’s website and interactions with members on social media, because it is up to Peloton owners to wipe down their bikes to prevent sweat from causing corrosion.

A former employee who worked at a Peloton call centre said the company declined to help some customers even if their bikes had been rusted when they received them.

“Some of these bikes were delivered with rust and we weren’t allowed to swap them out,” the person said. “Those were awkward conversations because I had no leeway to make any exceptions.”

Peloton, which before last week had not publicly flagged the problem, said: “If we become aware that this specific issue has caused a problem for any member, we will replace the bike.”

Additional reporting by Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson in New York

#techFT

#techFT brings you news, comment and analysis on the big companies, technologies and issues shaping this fastest moving of sectors from specialists based around the world. Click here to get #techFT in your inbox.