Higher rates don’t hurt growth stocks

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. On Monday, we took a sceptical look at the received wisdom that rising rates means falling growth stocks. We’re having another go at the idea today, to go along with a screed about the Federal Reserve’s ethics mess.

Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Death to growth stocks/duration dogma

A popular story about growth stocks is that they thrive when falling interest rates — especially falling real rates — make distant cash flows more valuable. The flipside is that higher rates increase the discount rate applied to distant cash flows, causing growth stock to underperform. In short, growth stocks’ long duration makes them rate sensitive.

The theory is simple and compelling, and the data, at first glance, appears to line up too. The chart below shows two decades of Tips yields (a proxy for real rates) plotted against the growth-heavy Nasdaq. Each dot is a day, and plots the Nasdaq’s level against the Tips yield that day. The relationship looks clear. Tips up, Nasdaq down, and vice versa:

But the more we think about this relationship, the more tenuous it seems. The rates-growth stock link is cyclical: it offers a prediction for growth stocks during the rising-rates stage of the business cycle. But the Nasdaq and Tips vary not just cyclically, but structurally. Big trends in the economy such as demographics and productivity lay behind both the rise in growth stocks’ prices and falling real rates. Both long-term trends could be driven by other causal factors.

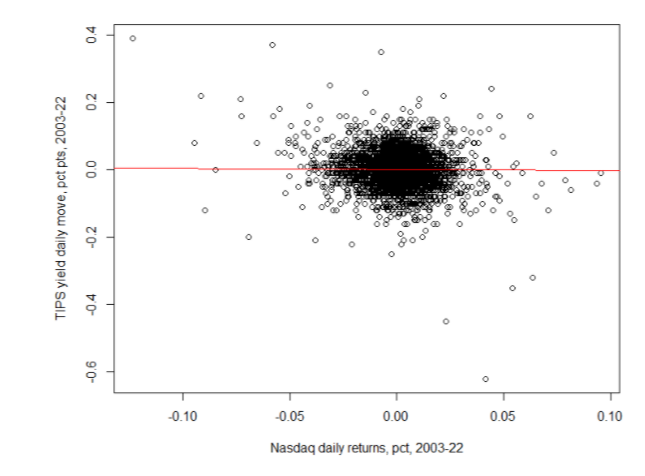

So we tried to isolate just the cyclical bits, by comparing daily Nasdaq returns to how much Tips yields rose or fell on the same day. If the simple real rates-growth stocks story is correct, days when Tips rose should often be days when the Nasdaq fell. Here is what we found:

There is a statistically significant inverse relationship here, but it is tiny. The red trend line slopes downward ever so slightly. Days when Tips are up do tend to be ones where the Nasdaq is down, using the word “tend” generously.

The rates-growth stock story is not utter bunk. Stock prices are the discounted present values of future cash flows. Discount rates do affect distant cash flows relatively more than imminent ones. But we don’t know for sure what the discount rate is, it varies for lots of reasons and the future cash flows are not fixed, either. So the relationship is certainly no iron law of markets. It is not even a particularly useful rule of thumb.

There are other, more intuitive reasons to doubt a durable link between real rates and so-called “long duration” growth stocks, many of which we discussed on Monday. But we failed to mention the most important one: no one thinks this way. “Oh, look, real rates are up by four-tenths of a per cent, to negative 1.3 per cent. The cost of money is really rising. I guess Tesla is no longer the good investment I thought it was. Sell!”

Yes, it could be that real rates are a factor in some traders’ models or spreadsheets, which could explain some of the recent price action. But believing this is different from believing the relationship is driven by durable financial logic. It isn’t.

Here is a much more likely thought pattern: “We’ve made a ton of money on these risky growth stocks. But now they are falling. We are heading into a policy tightening cycle, which are usually bad for risky stuff. Sell!”

The growth stocks-duration-real rates nexus is a thin idea that has hardened into dogma though repetition. Everyone should probably just drop it. (Wu & Armstrong)

Postscript: Richard Clarida

Colby Smith’s analysis piece about the departure of Fed vice-chair Richard Clarida is good and you should read it. Here is what led to his departure:

Clarida had already come under scrutiny in early October when he was found to have moved between $1m and $5m from a bond fund into a stock fund in February. The trades were made days before the central bank announced a huge dose of stimulus to support markets and the economy at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

But a previously undisclosed trade, omitted by Clarida due to what he said were “inadvertent errors”, showed he moved more than $1m out of the same stock fund just three days earlier.

. . . The Fed has declined to comment on the nature of Clarida’s newly disclosed transaction or how it related to the earlier explanation that the first questionable trade was part of a “pre-planned rebalancing” of his portfolio.

There are lots of subtle and slippery ethical issues that face anyone with tradeable inside information. Nothing is subtle about this case. It is batshit insane and makes the Fed look crooked.

There is no need to consider what Clarida’s intentions were, or whether his failure to disclose the second trade was truly inadvertent, or whether there was really “pre-planned rebalancing” involved. Ethics is a matter of appearance as well as intention. Here was a guy involved in the Fed’s deliberations about responses to the pandemic who was, at the exact same time, making millions of dollars in equities trades in both directions. Woah.

Clarida made the big equity fund sale (at least $1m, less than $5m) on the 24th of February 2020, just as the market was starting to fall sharply. He made the big purchase (at least $1m again, of the same equity fund) on the 27th. On the 28th, chair Jay Powell announced that the Fed stood ready to “use our tools and act as appropriate to support the economy”. On March third, the Fed cut rates. Much more stimulus was announced later that month. This guy was trading stocks in a big way when he had privileged insight into an imminent and enormous government intervention in the economy. This is a catastrophe.

The Fed has announced changes its trading rules since, requiring 45 days notice prior to trades and a one-year holding period. This was necessary, but is not sufficient. Fed officials should not be in control of their own portfolios at all. As I have argued before, key policymakers’ wealth should be in trusts, and those trusts should be designed with the Fed’s policy goals in mind. It strains credulity to think Fed officials forget all about their own financial positioning when they step into the Eccles Building. We need to be sure their biases are not determining policy.

One good read

How inflation creates risk in frontier stock markets: “Inflation is both unpopular and potentially destabilising . . . [and] political change can often trigger ownership change. In the worst-case scenarios, minority investors can be largely wiped out.”