Four trends that defined the 2021 energy sector

One thing to end the year:

Welcome to our last Energy Source newsletter until 2022.

Today’s bumper Christmas issue looks back on an extraordinary year in energy that saw everything from natural gas price crises, cyber attacks on pipelines, and David vs Goliath Wall Street battles, to emergency oil stockpile releases and big shale mergers.

In our second note, Amanda Chu has the answer to the question on everyone’s lips. Has Leonardo DiCaprio cracked the climate movie genre?

Thank you to all who read us this year, who commented on our articles, and have sent in ideas. Our numbers are still growing fast and we are grateful to every single one of you who signed up to the newsletter. I hope all of you stay safe and enjoy a decent break over the festive period. Merry Christmas to those who celebrate it. Happy New Year! We’ll be back in your inboxes on January 6.

This article is an on-site version of our Energy Source newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Tuesday and Thursday

The energy sector’s greatest hits of 2021

1. The energy price inflation crisis — and the cognitive dissonance it caused

In December 2020, the debut of Covid-19 vaccines ended the gloomy mood in the oil market. The good news sparked a stunning surge in oil demand, setting up a rally that looks likely to leave crude prices up about 50 per cent higher from the start of the year. Opec+ supply discipline and the drilling restraint in the US shale patch helped too. Plus, the cyber attack on the Colonial Pipeline sparked some fears of gasoline shortages in the US north-east, keeping prices elevated. Even as periodic Covid flare-ups, including the Omicron variant’s arrival, threatened the oil rally, sentiment remained bullish.

Wholesale gas and electricity prices even soared to record-busting highs as anxiety mounted about inadequate supply in Europe and Asia. In the UK, more than 20 energy providers went bust. In China, rolling blackouts brought a scramble for more international supplies. Fretful European governments that had been so focused on climate change announced subsidies for fossil fuel consumption. Germany stuck with its plan to shut down nuclear reactors, but its reliance on Gazprom’s gas began to look precarious, as geopolitical tensions threatened to bring new sanctions on Russian energy. Moscow played hardball, knowing it had the gas to fix Europe’s energy supply shortages.

Governments’ preoccupation with keeping natural gas, oil, and petrol prices low brought a display of cognitive dissonance. In Washington, for example, the Biden administration began the year promising sweeping clean energy reforms, new taxes on oil and gas pollution, and even toyed with imposing a cost on carbon. It ended 2021 by announcing the release of new crude from its emergency stockpile and a diplomatic deal with Saudi Arabia to ensure Opec kept pumping more oil into the market.

2. The year of the activist

Engine No 1’s victory in the shareholder battle with ExxonMobil was one of the most shocking events on the corporate calendar in 2021. The tiny hedge fund came from nowhere, owned just .02 per cent of Exxon’s stock, and deployed a fraction of the money Exxon spent fighting the proxy campaign. Its big win, securing three Exxon board seats, came on the same day that Chevron lost a climate-related resolution at its annual general meeting, and a Dutch court ordered Royal Dutch Shell to reduce its emissions more quickly than planned.

Still, it was Engine No 1’s coup that established a new activist template (and notched a mark for “engagement” investors in their debate with “divestment” campaigners). After the Engine No 1 vs Exxon showdown, listed oil companies’ management teams will be less willing to ignore shareholders’ climate concerns. Already, activists have come for Shell, commodity giant Glencore and Scottish energy group SSE.

Engine No 1 is still keeping a close eye on Exxon, Charlie Penner, who originated and led the fund’s campaign, told ES recently. But other activist targets will emerge in 2022 — including for Penner, who recently left Engine No 1. The question is whether last year’s big activist breakthrough only worked because of the oil crash — or whether rising oil prices and the return of chunky profits will keep shareholders quiet on climate issues.

3. Overpromising and underdelivering on climate

Climate took centre stage in 2021. From boardrooms to cabinet meetings, ambitions to combat global warming have never been more prominent. A landmark report from the International Energy Agency added urgency to the debate about how to curb fossil fuels and emissions. The agency said that if the world was to hit its climate targets, all new oil and gas projects must be shelved.

Yet for all the pledges and promises made in 2021, tangible progress was thin. The much anticipated COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, for example, brought some progress on climate finance, forestry and methane. But for an event billed as the last chance to keep global warming under control, world leaders fell short.

It was supposed to be the year the world agreed to ditch coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel. Leaders instead settled on phasing it down over many years. Greta Thunberg predicted the COP would be dominated by talk and little action: “blah blah blah”. She was not wrong.

And what about Joe Biden’s promise to bring the US back to the global stage on climate — to treat the issue as the “number one issue facing humanity”? The US rejoined the Paris accords. Biden made climate a cross-government priority. The administration introduced rules tightening emissions from cars and the methane spewed from oil and gas operations.

But the sweeping legislative changes needed to achieve the country’s emissions goals — a power generation sector free of carbon by 2035; a net zero economy by 2050 — did not materialise. The Build Back Better bill that would have pumped money into renewables on an unprecedented scale failed to pass muster in Congress.

It wasn’t all gloom for clean energy. Where the politicians failed, actual deployment did not. Clean energy seemed destined to account for almost all of the additions to US power generation during 2021. Capital markets continued to pour money into new clean tech and the capital costs for fossil fuel projects rose. Some feared a bubble in clean energy financing. Others saw a turning point.

4. The old energy comeback

And yet, while renewables started the year as the growth engine, the oil industry, decimated by the 2020 crash, has since come roaring back.

US oil stocks rose faster than clean tech or renewables. In the US, the XOP exchange-traded fund — often considered a proxy for market sentiment about oil and gas producers — was up 60 per cent since the start of the year. ICLN, BlackRock’s global clean energy ETF, was down about 30 per cent.

Having found religion with a new message of capital discipline, restrained growth and shareholder returns, a US shale sector famous for its output-growth-at-all-costs strategy started to churn out serious money. Investors also liked the consolidation in the US’s shale patch, where big producers got bigger and the weaker ones were winnowed out.

Soaring oil prices have driven huge profits among oil producers. But even with prices on the march, big public companies held the line and resisted the temptation to return to the “drill, baby, drill” mindset of old. Their privately owned counterparts, not so much.

How long the discipline holds is another question if oil stays high in 2022.

Another source of energy that had a good year was nuclear. Once the bogey man of environmentalists the world over, nuclear power has found support as a carbon-free source of baseload power.

In the US, money was pumped into propping up ageing and increasingly uncompetitive reactors. And new small scale reactors are increasingly being touted as part of a cadre of new technologies that will be key in the fight against emissions: from carbon capture to hydrogen.

Scepticism remains over what role any of these unproven technologies — still too expensive and unavailable at a commercial scale — will actually play in the coming years. But market enthusiasm was plain. VanEck’s nuclear power-focused ETF was up almost 150 per cent on the year. (Derek Brower and Myles McCormick)

‘Don’t Look Up’ shows climate change has a narrative problem

Adam McKay’s climate comedy Don’t Look Up premieres on Netflix tomorrow after a limited theatre run. The film stars Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence as two low-level astronomers who discover a comet that will destroy the earth.

We’ve seen space collisions on the big screen before, but Don’t Look Up stands out in its pivot from drama to comedy and using the approaching comet as a symbol of the world’s poor response to climate change.

“What I think is brilliant about this movie is that it’s a metaphor,” said Dale Jamieson, professor of environmental studies at New York University. “They don’t really make a movie that’s directly about climate change.”

When DiCaprio’s and Lawrence’s characters sound the alarm about the comet, they’re met with politicians who prioritise approval ratings and profit over planet protection. The “extinction-level event” quickly becomes mixed with conspiracy, partisanship, and science denialism — not so different from the climate response.

Does the metaphor work? Not really. While the comet in McKay’s film will hit the planet in six months, climate change is much more gradual. It’s more difficult to perceive and we can’t just blast the problem away without profoundly reshaping how we live and work.

“Unfortunately, McKay’s asteroid metaphor reveals just how misguided his understanding of the science and politics of climate change really is,” wrote Alex Trembath, deputy director of the environmental research centre the Breakthrough Institute, in Foreign Affairs last week.

Climate change has a narrative problem. Movie-goers want stories that are specific and immediate, a task that is difficult to accomplish with a threat like climate change that will take years to play out.

“This is such a big idea. How would you be able to put it into a story that people can actually consume, understand, and feel like they can do something about it?” said Tom Nunan, Hollywood producer and lecturer at UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television.

Climate movies do not need to be completely accurate to be persuasive. The Day After Tomorrow, another apocalyptic, celebrity-packed film that critiques the climate response, encouraged greater climate action — not that this has halted the rise in global emissions. Likewise, while celebrities stand in support of climate action, they also lead lifestyles and work in an industry with large carbon footprints.

“People don’t just respond to charts and graphs and numbers,” Jamieson said. “With climate change, [metaphor] is really probably the only way of effectively communicating about it.” (Amanda Chu)

Data Drill

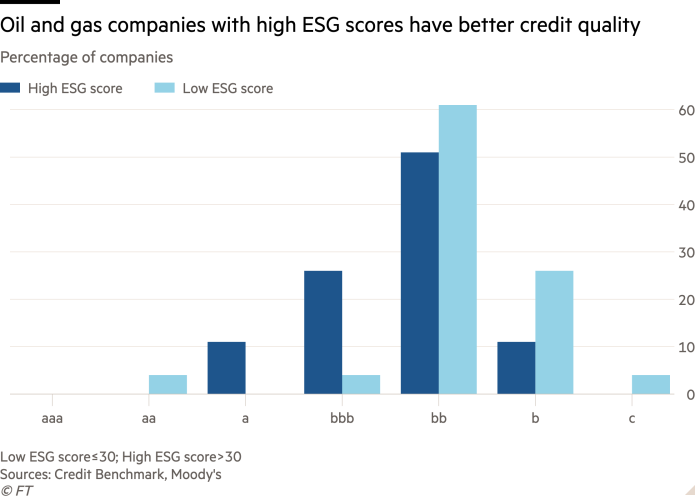

ESG scores are driving credit differences between oil and gas companies. Over a third of oil and gas companies with high ESG scores are investment-grade, compared with only 9 per cent of oil and gas companies with low ESG scores, according to an analysis by Credit Benchmark and Moody’s.

Their analysis suggests that company investments in ESG portfolios pay off. Having better credit quality means these companies have easier and cheaper access to funding. Oil and gas companies with high ESG scores saw a 17 per cent decline in credit risk in 2021, more than twice their low-ESG-scoring counterparts. (Amanda Chu)

Power Points

-

The EU wants to take €12bn from carbon trading revenues to pay off its pandemic debt.

-

Rio Tinto announces an $825m lithium deal as it looks to expand into battery metals.

-

Kyrgyzstan seized control of a Canadian mine owing to environmental and safety violations.

-

England slashed investment in water and sewage infrastructure despite declining ecological status and increasing water bills.

-

Four cities in America’s west are scrambling to secure water. (Bloomberg)

Energy Source is a twice-weekly energy newsletter from the Financial Times. It is written and edited by Derek Brower, Myles McCormick, Justin Jacobs and Emily Goldberg.

Recommended newsletters for you

Moral Money — Our unmissable newsletter on socially responsible business, sustainable finance and more. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here