Farmers fear for their land as hazelnuts spread across Italy’s hills

Giacomo Andreocci, who runs a small organic farm in the hills north of Rome, said he feels like part of a dying breed — thanks to a chocolate spread loved by millions.

The land around where he farms in the municipality of Vignanello used to be planted with a diverse mix including olives, vines and hazelnuts.

But lately, under a drive by Ferrero, the Italian company that makes Nutella, many of the surrounding valleys have been turned over to intensive hazelnut farming, with monoculture plantations replacing grassy pastures, small farms and rows of vines.

“Hazelnut cultivation has exploded massively, triggering such rapid change in the ecosystem around us that nature is no longer able to sustain it,” said Andreocci, walking along a track on the farm where he cultivates a range of crops.

“Hazelnut trees are now planted everywhere . . . and they are sucking up all our land’s resources.”

The changes that dismay Andreocci encapsulate a host of global themes, from food security and international supply chains to rising environmental concerns.

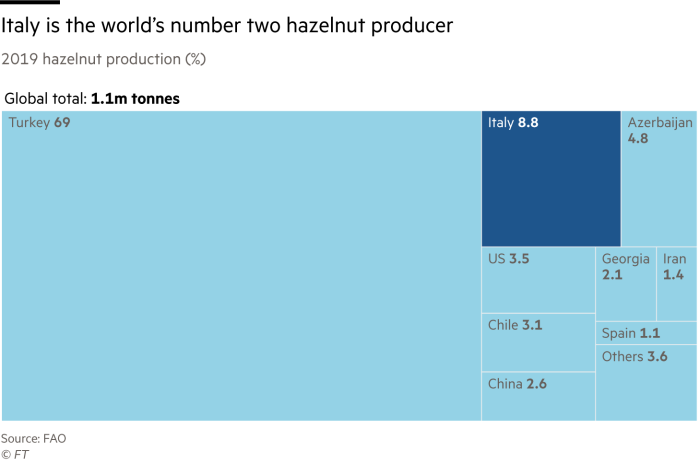

Ferrero’s decision to reshore some of its nut supplies from Turkey, its main supplier and the world’s largest producer, answered calls for manufacturers to shorten supply chains, boost local production, and raise the monitoring of sustainability and labour rights.

“Consumers in general are becoming more aware about how their product is produced and where it comes from,” said Ishan Das at Freeworld Trading, a UK nut trader.

But Ferrero’s shift has stoked environmental concerns and divided local communities into those who welcome the chance to maximise their incomes versus those who believe the resultant monoculture will create an environmental dead-end.

Hazelnuts have been grown around Vignanello since the 1960s. But under a 2018 plan dubbed Progetto Nocciola Italia, or Italian nut project, Ferrero set about boosting national production by 30 per cent to 90,000 hectares by 2025.

Pressure had been growing for the world’s largest buyer of hazelnuts to increase local procurement, with Italian politicians criticising the privately owned group for its reliance on Turkish supplies. Ferrero has also faced competition from Italian food group Barilla, which launched a spread made from “100 per cent Italian hazelnuts”.

Ferrero has said its reshoring plan focused on regions where hazelnut orchards could be integrated with other crops, adding that it also wanted to prevent non-cultivated agricultural land from being abandoned.

But environmentalist experts point out that this has led to local farmers planting nut trees where they do not grow naturally, such as near the sea. Intensive farming can also deplete underground aquifers and rob indigenous species of their habitat.

“The more we pursue this approach, the more we move towards a point of no return,” said Goffredo Filibeck, an environmental researcher at Tuscia University in Viterbo.

The environmentalists also say monocultures help spread plant diseases and insects, resulting in the greater use of pesticides and herbicides. Yet the Italian government’s national recovery plan has a €6.8bn agricultural component, part of which seeks to boost organic farming, improve biodiversity and reduce chemical use.

“When there’s biodiversity . . . you have a perfectly balanced system,” said Fernando Testa, an agricultural technician who works in Vignanello.

Ferrero strongly rebuffs claims that its actions damage the environment.

“Hazelnut cultivation is not destroying the Italian countryside; in fact, the country has a long history of hazelnut cultivation and is one of the main producing countries, with Italian hazelnuts being used by companies across multiple industries,” it said in a statement to the Financial Times.

The company said it has brought together agricultural and scientific experts to address sustainability challenges and that it promoted best practice through its sustainability programme. Many Italian farmers have also welcomed the income that nut growing provides.

“This debate is surreal,” said Lorenzo Bazzana of Coldiretti, the Italian farmers’ union. “Monoculture, whether of wheat, maize or vines, is nothing new . . . It is up to each entrepreneur to make their own choices, and have the responsibility to pursue correct agronomic techniques.”

The debate in Italy comes as the global nut supply chain faces growing scrutiny. While Ferrero monitors the sustainability of its supplies, Californian almond growers have faced a backlash over their intensive use of water, while cashew nut supply chains from Africa to South Asia have sparked concern over labour practices.

Growing more nuts in Italy helps Ferrero shorten some supply chains and increase its monitoring capability. It currently buys a third of Turkey’s annual crop, which accounts for 65-70 per cent of the world’s production of hazelnut, and also sources from Chile and Georgia.

But as Italy’s hazelnut industry ramps up, there is added pressure on the growers to maintain high-quality supplies.

“The market has to be fed constantly. It wants the perfect hazelnut and it wants it quickly,” said Marcello Lagrimanti, who started growing hazelnuts in Vignanello in 2017.

Surveying the farms around him, Andreocci said he understood the motivations of his neighbours but feared for what it would mean.

“From an economic point of view, right now [this] is the best thing there is. When a major company arrives, the local community focuses on a product that pays off. Jobs and wealth are created,” he said.

“But what do we leave to future generations? If we continue to plunder the land as we’re doing, there will be nothing left but desert.”

Follow @ftclimate on Instagram

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here