Clouds gather as delegates descend on Glasgow for COP26 summit

More than two years after Glasgow was unveiled as the host of COP26, 25,000 delegates from around the world are descending on the Scottish city for the most important environmental conference since the Paris accord was signed six years ago.

Yet even before the 14-day marathon gets under way on Monday, a year later than planned because of the coronavirus pandemic, the COP26 mood is already as gloomy as Glasgow’s inclement November weather.

Uncertainty about the ongoing reliance on coal domestically by China and India, as well as a failure to encourage more ambitious targets from other G20 countries such as Australia, has created anxiety that the summit could prove to be a repeat of the unsuccessful Copenhagen meeting more than a decade ago.

Yet John Kerry, US climate envoy, told the Financial Times that COP26 was always going to be extremely challenging, since the negotiators at Paris were tasked with agreeing an aspiration — limiting global warming to “well below” 2C, or ideally 1.5C. The job in Glasgow, however, is to finalise how to achieve this and turn it into action.

“I think everybody would agree this is harder [than Paris], because it’s got more real and focused,” said Kerry, who led the US delegation to the French capital.

“The science is clearer, the steps people have taken are clearer, and the absence of [those] steps are clearer,” he said in an interview. There was now a “much more clear choice in front of countries as to what they need to do . . . That makes it harder, because there are real economic choices.

“I think that puts pressure on different countries in different ways.”

While Joe Biden, US president, and Emmanuel Macron, his French counterpart, will join host Boris Johnson, UK prime minister, and more than 100 other world leaders, the top-level discussions will take place without China’s Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin of Russia, who will not attend in person because of Covid-19. The no-shows will send negotiators and sizeable delegations in their place, but their absence could make negotiations harder.

Delegates who do make it to Glasgow will be tasked with agreeing a set of rules to implement the 25-page Paris accord. The previous summit, in Madrid in 2019, failed to resolve the controversial issue of carbon markets, sparking anger from green groups towards the likes of Brazil and Australia for their perceived roles in stalling the talks.

Glasgow picks up where those talks left off: agree how countries should report and verify their greenhouse gas emissions, create a framework for global carbon markets, often referred to as “Article Six”, and lay the foundations for ensuring that warming can still be limited to 1.5C.

Support for a global methane pledge is also building, with 34 parties, including the EU, signing up to a pledge to slash global methane emissions by 30 per cent from their 2020 levels by 2030.

“This is a delivery COP, not a treaty COP [like Paris],” said Nick Stern, chair of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change at the London School of Economics and Political Science and author of a landmark report in 2006 into climate change economics. “The question is, can we deliver?”

The thorny issue of climate finance will be another sticking point, with rich nations this month admitting they had fallen short of a promise to developing countries to deliver $100bn by 2020. That goal, a key element of the Paris accord, will be pushed back to 2023.

The UK’s high Covid-19 infection rate will also cast a pall over the summit, where attendees will have to take daily lateral flow tests to be admitted.

There are reasons to be optimistic. The world’s attention is now much more focused on the accelerating threat from climate change, after a series of natural disasters that have ravaged swaths of the planet. This will provide a powerful incentive for leaders to strike a deal.

Most of the world’s major economies have also over the past year agreed targets for carbon neutrality by the middle of the century. The likes of Saudi Arabia and Australia have signed up in recent days, although critics say it is not clear how they will achieve their decarbonisation plans.

An array of corporate leaders will also attend, underlining the pressure that consumers are putting on businesses over climate change. Ramon Laguarta, chief executive of soft-drinks group PepsiCo; Anand Mahindra, head of one of India’s largest industrial groups, Mahindra & Mahindra; and Ignacio Galan, chief executive of Iberdrola, are among those who will travel to Glasgow.

Another new factor is the vocal youth climate movement that has thrust itself into the spotlight in recent years, inspired by the activist Greta Thunberg, while groups such as Extinction Rebellion are taking more direct action. Thunberg is expected to attend COP26.

The mood in Glasgow will in part be determined by what happens at this weekend’s G20 summit in Rome. Host Italy wants G20 nations to agree to end financing for international coal power plants, but coal-reliant nations such as India are pushing back.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Christiana Figueres, former head of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the body behind the COP gatherings, noted that the G20 meeting just before Paris in 2015 was “absolutely disastrous” on climate.

“I don’t think that whatever comes out of the G20 should actually cast a shadow on COP26,” she said. The key question is not what they do collectively in Rome, but what “each of them” commits to doing in Glasgow.

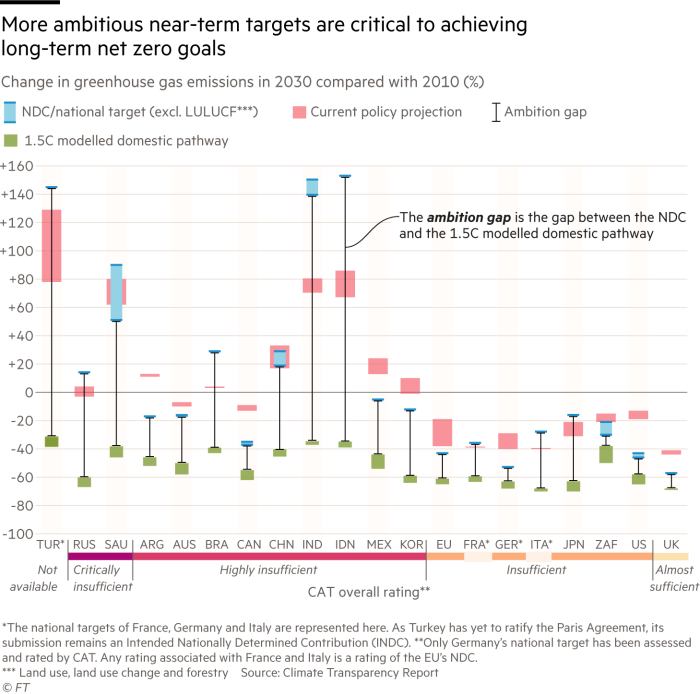

This week, Patricia Espinosa, current head of the UNFCCC, warned word leaders that they were still “very far away from where we should be”, referring to a UN analysis that climate targets submitted by countries so far put the world on track for an overall rise of 2.7C of by the end of the century.

Countries needed to act now to prevent this from happening, she said, starting in Glasgow. “Overshooting the temperature goals will lead to a destabilised world and endless suffering,” she said. “Especially among those who have contributed the least to the greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere.”