Brothers-in-law at war: family feud at Velodyne illuminates Spac pitfalls

David Hall and Brad Culkin are inventors, longtime colleagues and brothers-in-law.

But after a Spac deal and a boardroom bust-up at their company, Velodyne Lidar, they are now, in the words of Hall, locked in a “fight to the death”.

Hall, who founded the 3D sensor business, was ousted as chair earlier this year but remains the largest shareholder and is now determined to strike back against Culkin, who took over as chair, and anyone else on the board who helped remove him.

Last week, Hall wielded his majority voting power to install Eric Singer, an activist investor, on to the board. “He’s going to drive those cockroaches out of there,” said Hall, in an interview with the Financial Times. “I want them gone and to never hear from them again for the rest of my life, and my children’s lives as well.”

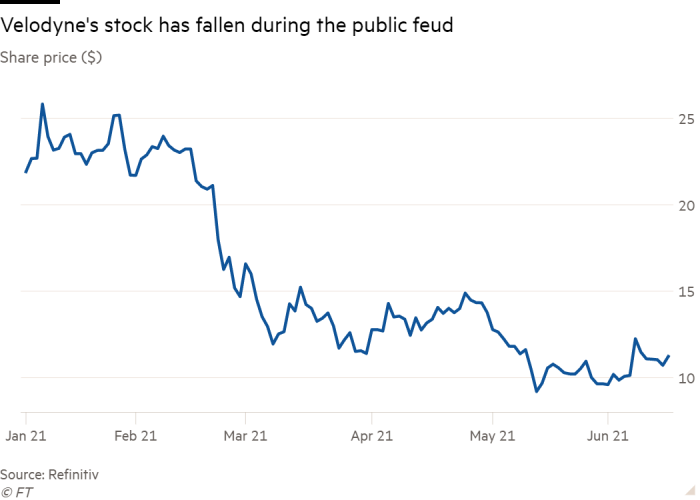

The developments at Velodyne are another example of the pitfalls of special-purpose acquisition companies, which have provided a quicker route to public markets compared to traditional listings, but which have also been used by high-risk, founder-controlled businesses. The company’s share price has fallen more than 50 per cent this year during the public dispute.

A spokesperson said the company continues to execute “a strategy designed to drive long-term growth for the company [ . . . ] with the highest standards of corporate governance”.

Falling revenues

Velodyne is the leading US manufacturer of lidar systems, the rotating laser devices used by self-driving vehicles to “see” roads and obstacles. Ahead of its arrival on the public markets, through a $1.6bn deal with a Spac called Graf, regulatory filings described it as a “fast growing business with strong momentum”.

But the company’s troubles stretch back for years, according to regulatory filings and people familiar with the company.

Hall set up Velodyne in 2016, raising an initial $150m from Ford and China’s Baidu. The investors also became important customers, buying millions of dollars worth of products.

Velodyne made more than $180m in revenues in 2017, according to filings, largely from one-off sales to research teams at companies such as Uber that were developing self-driving cars. That year, Velodyne’s lidar sensors sold for a weighted average price of nearly $18,000 each.

But as rivals flooded the market, the price of lidar sensors fell sharply. Velodyne said it had proactively cut its prices to increase the adoption of the technology, but by 2019 its revenues had fallen by more than 40 per cent.

In 2018, the company accused Hesai, a Chinese rival that also received funding from Baidu, of reverse engineering its spinning lidar sensors. Last year, it settled the dispute with Hesai and with another Chinese company, in exchange for licensing and royalty fees.

But Hall said the alleged theft of Velodyne’s designs had “ruined” the market for lidar.

‘A family business’

Meanwhile, several people familiar with the company accused Hall of running it as a family business, at times employing his relatives and friends in senior roles.

Regulatory filings showed that Hall and his wife Marta, who remains on Velodyne’s board, borrowed from the company to fund the $23.4m purchase of a building in San Jose, California, that served as its headquarters. A company owned by the couple then charged Velodyne millions of dollars in annual rent for the use of the building.

Last month, the Halls sold the property for $51.4m, returning more than double their initial investment. Hall said the deal had been “dumb luck” and that he charged the company below-market rent.

Responding to questions about the jobs held by his family members, Hall said: “It is marginal nepotism, and it is getting a little out of control. I am going to rein that in some day.”

The road to the public markets

In January 2020, Hall stepped back from day-to-day management, promoting Anand Gopalan to chief executive as the company began to consider an IPO. Hall said at the time that Gopalan was “the right executive to lead Velodyne in its next growth phase”.

Velodyne held preliminary discussions about an IPO, but investors had difficulty valuing the company after several years of revenue declines, said two people familiar with the process.

As the pandemic hit, another option presented itself: Spacs, or blank-cheque vehicles raised for the purpose of merging with a company and bringing it to public markets.

Graf Industrial Corp, which had already abandoned talks with a polypropylene recycling company, began discussions with Velodyne in May. By June, the companies had begun soliciting investors for additional backing to add to the Spac’s cash contribution, aided by advisers at Bank of America and Oppenheimer.

An investor presentation predicted Velodyne’s revenues would begin growing again and reach more than $680m in 2024, with more than half of business coming from new multiyear agreements, software sales and subscriptions. In 2020, the company had revenues of $94m.

The deal was announced in July, and in the weeks leading up to Velodyne’s listing in September, the vehicle’s share price briefly reached $32. Culkin, who co-founded with Hall an audio company from which Velodyne was spun out, emerged with millions of shares and a seat on the board.

Ford, meanwhile, negotiated an exemption to lock-up agreements that typically restrict insiders from early trading, and sold its entire stake in Velodyne in the fourth quarter. Ford, which is still using Velodyne’s technology, has said the sales were “consistent with our efforts to make the best, highest use of capital”.

The battle for control

In the months after going public, Hall pushed for changes to the board that would have allowed him to appoint six out of eight directors and fire the chief executive, according to Velodyne.

The board’s audit committee began investigating Hall and his wife, claiming in February that they “behaved inappropriately with regard to board and company processes”. Velodyne removed Hall as chair without publicly providing specifics of the investigation’s findings.

In a statement to the FT, Velodyne said the alleged misconduct by David and Marta Hall “dramatically increased” after Hall’s board proposals were rejected. Velodyne said every member of the board other than Marta Hall rejected Hall’s claims, which it said contained “unsupported accusations”.

Following his removal, Hall accused Culkin of taking “several liberties with the truth” and acting as a “rubber stamp”. Culkin did not respond to requests for comment.

One day after the annual shareholder meeting last week, Velodyne announced it had begun arbitration proceedings against Hall, alleging breach of contract and the theft of trade secrets.

In a separate statement, the company said Hall had copied “hundreds of thousands” of Velodyne documents on to at least one external hard drive before returning his company laptop. Through a spokesperson, Hall declined to comment on the arbitration.

Hall said he had been misled by lawyers and Spac executives during the merger process, which he believed would allow him to retain control over the company. Graf and Gunderson Dettmer, the law firm that represented Velodyne during the Spac discussions, declined to comment.

Investors nurse losses

Meanwhile, investors have posted complaints on the message board Reddit, and have called in recent weeks for the Halls to abandon their battle with the company. Shares were trading at about $11 on Wednesday.

Outside observers predicted that several companies that have struggled since merging with Spacs may become prime targets for activist shareholders. Many have yet to find commercial success for futuristic technologies and are still led by relatively inexperienced teams.

“That’s all the ingredients you need for volatility and activist interventions,” said Ethan Klingsberg, a partner at the law firm Freshfields who advises boards on corporate governance matters.

Additional reporting by Sujeet Indap in New York