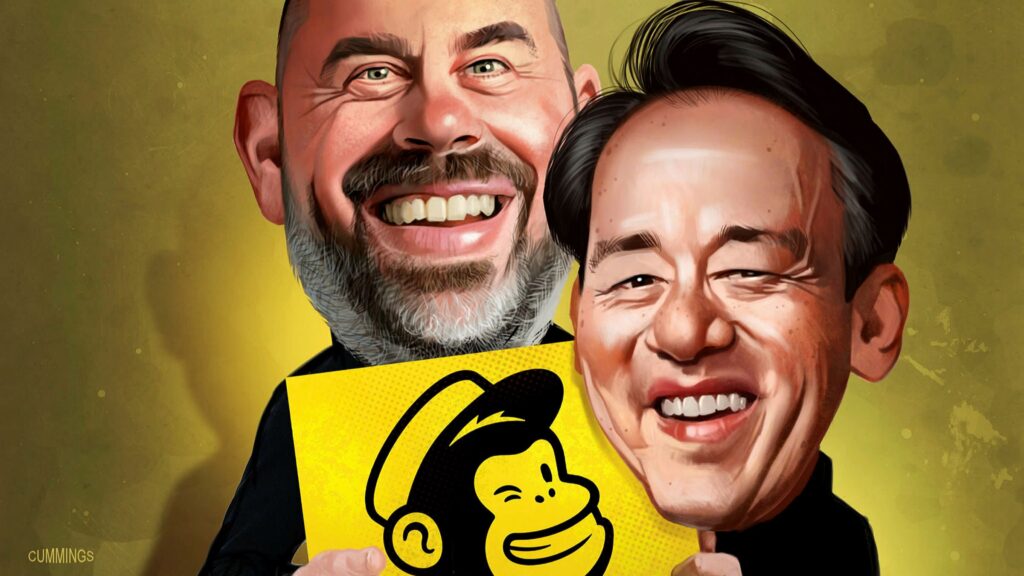

Ben Chestnut and Dan Kurzius, the men who made MailChimp

Ben Chestnut and Dan Kurzius frequently get asked why they refused to take venture capital for their email marketing company, MailChimp. The answer became obvious this week.

On Monday, the tax software company Intuit announced it would acquire MailChimp for $12bn in cash and stock, an extraordinary outcome for a start-up that had never taken a dime from investors.

The sale effectively turned the founders into multibillionaires overnight. Because they never sold any of the company to venture capitalists — or granted stock options to employees — their stakes in the company came out to roughly $5bn each.

For the Atlanta-based founders, the deal was evidence that it does not necessarily take venture capital or a Silicon Valley address to produce a huge tech business.

“I kind of feel like I had my head down, tweaking things, improving things, and then I looked up and bam, it’s a $12bn company,” Chestnut tells the FT.

Both founders have pointed to their parents’ small businesses as inspiration. Forty-seven-year-old Chestnut, raised in the rural Georgia town of Hephzibah, has recalled memories of sweeping up hair at his mother’s salon. Kurzius, 49, a collector of vintage skateboards who grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, has talked about how his father’s bakery struggled to compete against larger chains.

The two first crossed paths at mp3radio.com, a dotcom era venture associated with the Atlanta media conglomerate Cox Enterprises. Chestnut hired Kurzius as a software developer after he bluffed his way through the interview, having no previous experience in coding.

Gregg Lindahl, the former chief operating officer of mp3radio.com, says Chestnut stuck out with a flair for design, even for mundane tasks.

“I had the best PowerPoints on the planet. I’m quite sure of it,” Lindahl says.

When the venture folded, Chestnut and Kurzius struck out on their own, starting a design agency. They began working on websites for dotcom companies, until that work dried up and airlines and real estate companies became their biggest clients.

Eventually, the duo began contemplating a pivot. It turned out that another part of the company had been quietly growing: an email marketing service called MailChimp, which they had offered for a nominal fee.

In 2007, Chestnut and Kurzius decided to focus their full attention on MailChimp. Investors began taking an interest, believing the company could grow quickly by selling to large enterprises, a prospect that irked the founders.

“It felt like they were more like alien beings from another era trying to tell me how to run my business,” Chestnut told the LinkedIn founder and venture capitalist Reid Hoffman on a podcast.

Around this time, Chestnut, who is the public face of the company, says he also began thinking about selling MailChimp for close to $4m. The company started to stagnate while he agonised over whether to sell, before he finally abandoned the idea.

After adopting a business model in which the basic MailChimp product was given away for free and paying users were enticed with extra features, the service began growing even faster.

Now Chestnut says he has begun to envision a future beyond MailChimp. “I love what it does, but it’s not me. I’m a human being, you know.”

Pamela Walker, chief executive of the Atlanta-based non-profit ArtsNow, says Chestnut and his wife Teresa have donated money to the organisation earmarked for work on arts-based education and technology in Hephzibah, where they met in high school.

“They do not want the recognition,” Walker said. “They do not want the accolades.”

Meanwhile, MailChimp’s founders have become heroes to the so-called bootstrapping community, which eschews venture dollars in favour of profits and greater control over their businesses.

Wade Foster, chief executive of Zapier, a software company that has partnered with MailChimp, says he was surprised the founders decided to sell, but doubts it had anything to do with money. “There were probably other reasons they felt this was a good outcome for MailChimp, for the customers and for everyone.”

Because MailChimp did not reward employees with stock options, they do not stand to benefit from the million-dollar paydays associated with big tech sales. The deal includes a total of $500m in stock-based rewards, and MailChimp has paid up to 25 per cent of annual profits into employee retirement accounts since 2012.

“If you’re with us over the 21 years as a privately held company with no interest in an exit, then it makes a lot more sense to share profit in your hands now,” Chestnut says. The company will also pay out cash bonuses to employees.

Because MailChimp has never taken money from investors, Chestnut says he has never had to produce formal financial reports. MailChimp generated $800m of revenues last year, comparable to several public software companies with even larger market values.

“I would look at the previous balance, and then I would look at this month’s balance, and I would want to make sure that this month was greater than last month,” Chestnut says. “That’s all I ever did.”

This article has been updated, correcting the surname of the chief executive of Zapier