Airbus gears up for hydrogen jet as fuel of future edges closer to reality

Hydrogen’s moment is fast approaching, according to Airbus. Talked about as the fuel of the future for years, Guillaume Faury, the planemaker’s chief executive, says the company is ready to start building a hydrogen-powered commercial airliner before the end of the decade.

Europe’s aerospace champion is increasingly confident that 2035 is a “fair and realistic perspective” for a hydrogen plane to enter service, despite scepticism among other industry leaders about how quickly the gas can make an impact on aviation emissions.

“We don’t need to change the laws of physics to go with hydrogen. Hydrogen has an energy density three times that of kerosene — [technically it] is made for aviation,” Faury told reporters at an Airbus event on sustainability in Toulouse.

Faury’s comments signal Airbus’s growing confidence that the company will be able to tackle the complex engineering and safety challenges needed to make hydrogen-powered aircraft work. Faury warned, however, that government and regulatory support would be needed.

Airbus, said Faury, needed to have a “degree of certainty” of the regulatory environment and the availability of the fuel by 2027/28, when the company will have to decide whether or not to invest billions in a new hydrogen plane programme.

“This [decarbonisation] challenge is not only about an aeroplane, it’s about having the right fuels — hydrogen — at the right time, at the right place, at the right price and that is not something that aviation can manage alone,” he said.

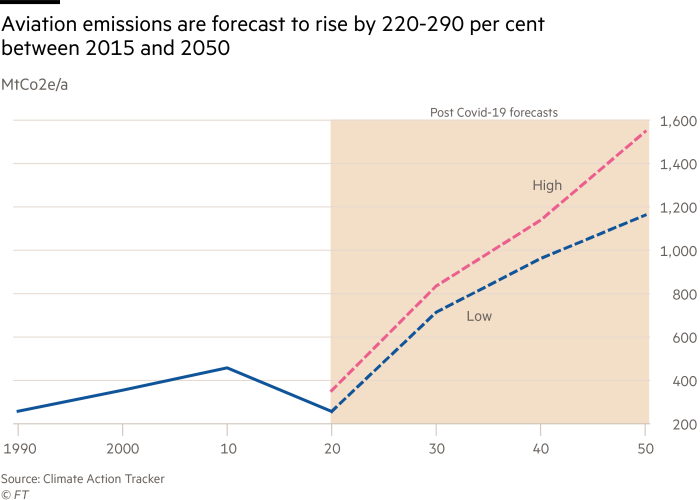

Faury’s remarks underline the increasing urgency in the aviation industry as it strives to meet zero-emission targets by 2050. Before the pandemic led to the grounding of much of the global aircraft fleet, aviation accounted for roughly 2.4 per cent of global emissions.

The pressure to curb emissions has only accelerated since the crisis. The summit in Toulouse brought together airlines, airports and policymakers in an attempt to galvanise a co-operative approach on how to burn less kerosene.

Aerospace companies are working on a number of different technologies, from “sustainable aviation fuels” to electric batteries and hydrogen. Rolls-Royce, the UK aero-engineer, is currently testing an all-electric plane. Many are also backing new start-ups that promise a revolution in urban air mobility through the use of air taxis.

In Toulouse, John Holland-Kaye, chief executive of Heathrow airport, called on airlines to help trigger the use of sustainable aviation fuels, telling the audience: “If we don’t get to net zero by 2050, we won’t have a business. The faster we scale up sustainable aviation fuels, the faster we can decarbonise aviation.”

Airbus, along with its peers, agrees that there is no one “silver bullet” and that a variety of solutions will be needed to address the decarbonisation challenge. It too is working on different technologies, including sustainable aviation fuels.

But differences remain about the speed at which the industry can make hydrogen happen and Airbus’s enthusiasm is not shared by everyone.

“At Airbus, we decided to take the bull by the horns,” said Faury. “We’ve seen the engine makers significantly change their views on hydrogen, which is very positive.”

Engineers at the European plane maker are working on several different zero-emission concepts, all of which rely on hydrogen as their primary power source.

The number of technical challenges are large. Sabine Klauke, Airbus chief technical officer, said the need to liquefy the hydrogen and store it at minus 253 degrees centigrade was an obvious hurdle. The special double-skinned tanks needed to contain the substance are four times the size of conventional fuel storage and would need to be accommodated into the body of the aircraft.

Even if the technology hurdles can be overcome, the investments needed to build up the supply of “green” hydrogen made by renewables, to change the storage requirements at airports and associated infrastructure, will be enormous. Following the pandemic Europe’s governments, notably France and Germany, have committed significant sums towards helping the industry decarbonise, including through the use of hydrogen.

Airbus says it is likely initially to produce a regional or shorter-range aircraft.

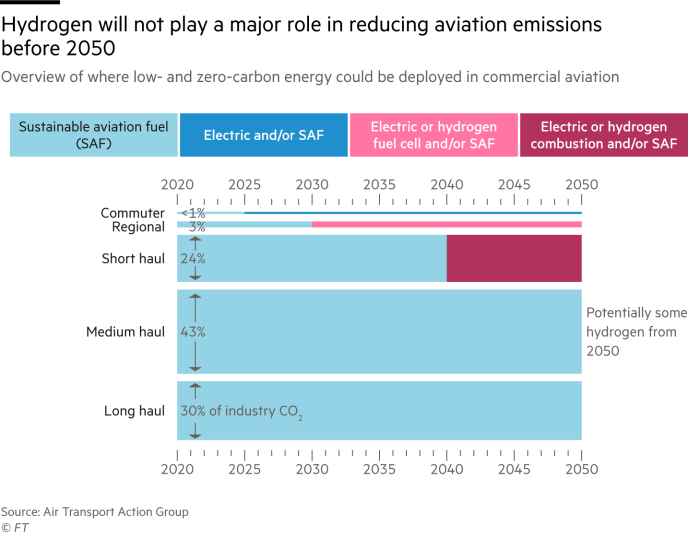

Detractors point out the really big dent in the industry’s carbon footprint will only come from tackling the most polluting segment of aviation — 73 per cent of carbon dioxide emissions come from medium and long-haul flights, according to the Air Transport Action Group.

Alan Epstein, a former industry executive and professor of Aeronautics at MIT, argues that sustainable aviation fuels are the only “practical solution” to greening commercial aviation.

“Not only do you want to reduce CO2, you want to come close to eliminating it by 2050. Time is of the essence and solutions that require replacing trillion dollars worth of aeroplanes and airport infrastructure with technology that won’t be mature for a decade or two won’t get you there,” he said.

“The economic feasibility of hydrogen airliners in the next 20 years is more strongly influenced by national policy and regulation than it is by technical or financial reality. It is those regulations that will establish any economic basis,” Epstein added.

David Joffe, of the UK’s Climate Change Committee, the advisory body to the government, is similarly sceptical that hydrogen is the answer.

“We need solutions earlier than that,” he said, pointing out that planes bought today will “still be operating in 2050”.

Despite the current high cost of sustainable aviation fuels compared with conventional kerosene, the committee estimates that in the longer term, once these fuels are deployed at scale they would add about £80 to the cost of a return ticket from London to New York.

At Airbus’s rival Boeing, engineers are also working on technologies such as hydrogen and electric propulsion, but the company has made clear it believes the potential for the gas is some time off.

“My path will not include — between now and 2050, will not include the introduction of a hydrogen-powered aeroplane in the scale of aeroplanes that we’re referring to,” Boeing chief executive Dave Calhoun told an analyst conference in June.

Instead, he cited fleet renewal, as airlines upgrade to more efficient aircraft, and sustainable aviation fuel as critical steps in the immediate future.

“The technologies work, we know it,” he said of sustainable fuels. “The question is cost and scale.”

As the industry emerges from the crisis wrought by the pandemic and airline managements start to think again about growth, the one thing that is clear is that the industry needs to change.

“Our passengers expect change. If you don’t do the right thing, you might not have a business,” said David Morgan, director of flight operations at easyJet.