Investor scepticism on ESG points to a maturing market

After more than two years of soaring clean energy stocks and an avalanche of green product launches, the backlash against sustainable finance has arrived. But, while some worry that environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing is losing credibility, others believe a healthy dose of scepticism indicates that greater rigour is entering the market.

With some ESG funds still holding shares in oil or even coal companies, one concern is that unclear definitions of ESG, along with pressure to meet high demand, is resulting in investment products that are not as green as they claim to be.

In August, so called “greenwashing” came under the spotlight after Desiree Fixler, DWS’s former global head of sustainability, made a statement to the Wall Street Journal based on internal emails and presentations alleging that the German asset manager had misrepresented its ESG capabilities.

DWS had hired Fixler the previous August to demonstrate to the world that it was serious about ESG. “I was very aware that there were problems,” says Fixler. “The approach to ESG was fragmented and my job was to pull it all together.”

She and a team of colleagues ran an analysis of the number of portfolio managers using ESG criteria in their investment decisions. “The firm had no tracking system, so we could only approximate how many portfolio managers were considering ESG factors,” she says. “But, through interviews, document reviews and portfolio positions, we concluded that only a small percentage were doing so.”

Fixler first presented her concerns to the executive board in November 2020 and again in February. On March 11, however, she was fired, a day before the firm released its 2020 annual report, which claimed that assets of €459bn (more than half its total under management) were being assessed using ESG criteria.

“They saw the evidence in the internal risk management and senior management reports and, on March 12, they crossed the line,” she says.

“I’d expected to see some gaps and weaknesses in the ESG methodologies. What I didn’t expect was the misstatement of capabilities and numbers.”

In a statement made in August, DWS said it stood by its annual report disclosures. “We firmly reject the allegations being made by a former employee,” it said. “DWS will continue to remain a steadfast proponent of ESG investing as part of its fiduciary role on behalf of its clients.”

The firm said it had always made clear that it distinguished between “ESG integrated” assets, which consider sustainability issues as part of the overall investment process for mainstream funds, and ESG assets — specialist products with a mandate to focus on sustainable investing.

DWS is now the subject of investigations by BaFin, the German regulator, and the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Department of Justice in the US.

This is a wake-up call, says Bob Eccles, a visiting professor at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School and an expert on sustainability. “If you’re calling something ESG, you have to be clear on what that means,” he says.

But, while DWS hit the headlines, it is not alone in prompting questions over standards in the rush to meet surging demand. According to industry body the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, assets under management in the sector reached more than $35tn last year.

“There are people trying to get this right but there are other cases . . . where people have taken shortcuts just to pump out the product,” says Fixler. “It’s a shame — we have an urgency to fix our carbon footprint and inequality but we’re not going to do it through shortcuts.”

Regulators are starting to act. For example, through the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), asset managers must meet tough standards if they want to market a fund as a sustainable product.

And, in the US, heightened scrutiny is coming from the SEC which, in April, issued a risk alert highlighting the dangers to investors of poor definitions of ESG.

However, while critics are becoming more vocal, some argue that growing scepticism about green finance is a positive development as it reflects a maturing of the market.

“I appreciate the fact that this is being tabled because it means we’re all getting more rigorous,” says Kirsty Jenkinson, head of sustainable investment and stewardship strategies at Calstrs, the Californian teachers’ pension fund.

She points out that, for many years, the complaint was that there were too few ESG investment products in the market. “I’d rather have it this way because then the onus is on us to make the best choices,” she says.

Others welcome the end of an era when few investors or asset managers saw green finance as a viable market. “The good news in all of this is that it wasn’t all that long ago that if you said ‘green’, people thought it was trading away returns,” says Eccles.

But mainstream investors’ embrace of ESG has prompted another worry: that too much emphasis is being placed on the financial returns, rather than on whether the funds are making any difference to global environmental problems.

More from this report

Jason Hill, a financial services expert at PA Consulting, believes asset managers who can demonstrate this will benefit in the long run. “Step one is measuring carbon impact, but what we want is the year-on-year trends of the impact, which we’ve not seen yet,” he says. “This will give a huge competitive advantage to those that get that out there. At the moment, it’s ‘trust us’ — but soon it will be ‘look at us’.”

Given what it will take to achieve rapid decarbonisation, more accurate measurement of carbon emissions may also reveal an uncomfortable truth: a short-term rise in emissions resulting from the use of steel, concrete and other energy-intensive materials and processes needed to expand clean energy infrastructure.

This is why simply measuring carbon emissions is insufficient, says Charles Donovan, visiting professor of finance at the University of Washington’s Foster School of Business. “How are we going to know the difference between emissions that are increasing on the back of a substantial transition versus emissions that are increasing because we’re getting nowhere? That’s not going to be easy to unpick.”

For this reason, he says, the focus should not be on assessing whether one investment portfolio is greener than another. “It’s important to think about the indicators that a global energy transition is occurring, rather than whether a portfolio has managed to move the chairs on the Titanic to make it look like it’s a real solution,” he says.

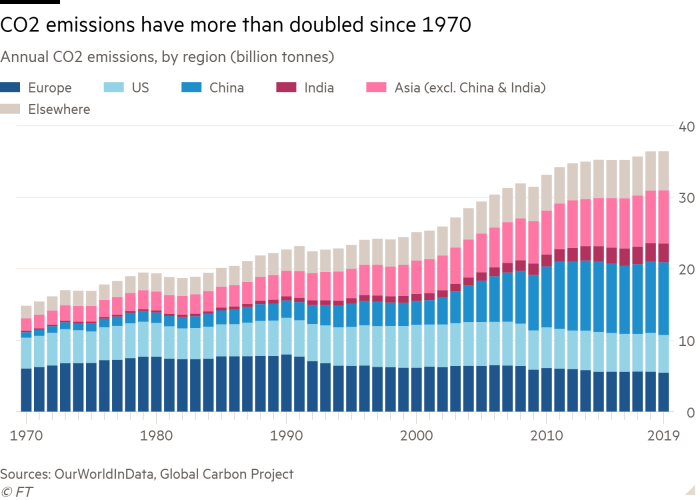

Even so, this leaves many frustrated that the wave of green investing appears not to have led to any significant reduction in global carbon emissions, which have risen inexorably for decades.

Jenkinson shares their frustration, but points out that the large-scale flow of funds required for the transition to a low-carbon economy began only recently.

“Yes, we need to make sure there’s strong accountability,” she says. “But you don’t create wholesale industrial, agricultural and economic change in five years — it probably takes a generation. So we need to let it grow up before we completely shoot it down.”