Innovation still requires smart, even barmy, innovators

Innovation updates

Sign up to myFT Daily Digest to be the first to know about Innovation news.

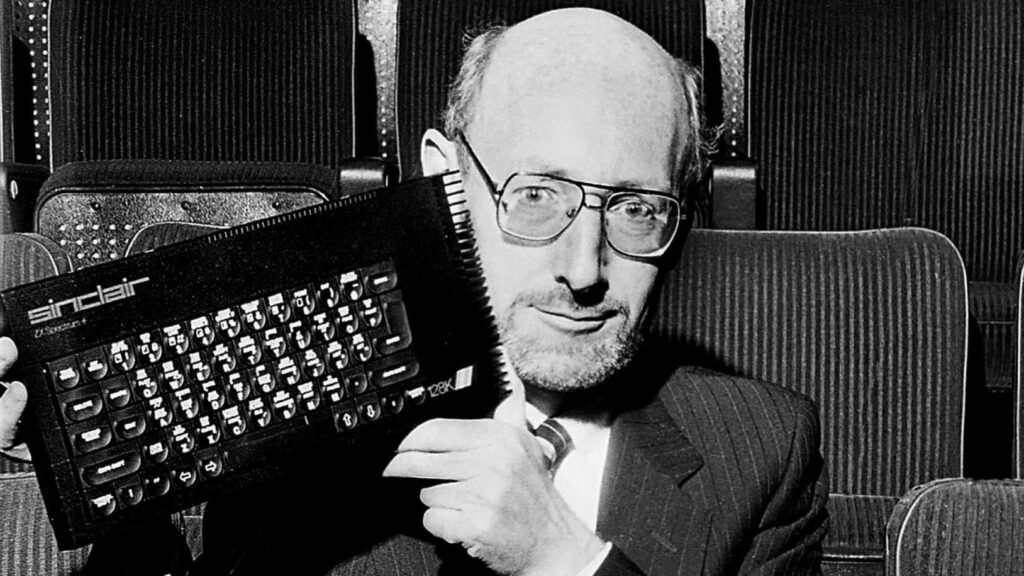

It has been inspiring to read the tributes paid to Sir Clive Sinclair, the quixotic British inventor of the ZX Spectrum personal home computer, who died last week. For countless users, the launch of Sinclair’s cheap and clunky machine in 1982 was their first encounter with the magical possibilities of computers. “An absolute genius with just the right amount of barminess to be a proper British boffin,” one commenter wrote on The Register’s memorial page.

Sinclair was as famous for his failures as for his successes. But that only seemed to feed the admiration of his followers. To be kind, his C5 electric tricycle and portable television were both ahead of their times. To be less kind, they were both terrible products. Still, the inventor’s fascination for technology and his rustproof optimism enthused so many others to experiment and to dream.

Although we love nothing more than a colourful personal story and to trumpet the role of outstanding individuals in innovation, a growing body of research suggests that they are largely incidental to the process. If John Smith had not invented this bit of kit today then Jane Smith would probably do so tomorrow. From this perspective, technological improvements result from an almost mechanistic process, the accumulation of small, incremental, collective gains rather than from a sudden flash of individual inspiration.

A prime example has been the way in which researchers in several different companies and institutes developed different Covid-19 vaccines from the same base of scientific knowledge. This chimes with the musician Brian Eno’s idea that the collective output of a creative community, what he calls the scenius, is more important than any one individual’s genius.

This school of thought has been underpinned in a new academic paper by a team of researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, based on empirical data on the improvements in 30 technological areas over the past three decades or so. “A lot of breakthroughs happen because so much is happening in the same space at the same time and someone is going to figure it out,” says Anuraag Singh, one of the paper’s authors. “The patterns of innovation are fairly constant over the long term.”

Intriguingly, this MIT team has used the data to launch TechNext, a software service that aims to predict the likely improvements of 1,757 technological domains in the future. The most striking advances, they suggest, will come in software and networking technologies while the slowest will be in hardware: it is particularly tough to bend the laws of physics. Although the paper’s authors stress they cannot predict adoption rates of new technologies, they suggest fully autonomous vehicles are not likely to zoom round the corner soon, while blockchain technology may improve faster than people commonly suppose.

Such research highlights the distinction that is sometimes drawn between invention and innovation. Breakthrough technological inventions do not instantly lead to profitable innovation. Indeed, successful innovation often comes from mashing together known technologies in novel ways to offer a better service or to imagine an alternative business model. Innovative companies as varied as Uber, Spotify and Domino’s Pizza exemplify the trend.

However, Melissa Schilling, a professor at New York University Stern School of Business, resists the idea that exceptional individuals do not count for much in the innovation equation. It is true that incremental technological improvements may be driven in largely predictable and programmatic ways, she concedes, but this only tells part of the story. In her book Quirky, Schilling explores the traits and foibles of eight breakthrough innovators, including Thomas Edison, Marie Curie, Nikola Tesla and Elon Musk. She found almost all of them to be instinctively solitary, manic eccentrics or misfits, driven by a sense of purpose and hard work.

“Breakthrough innovation comes from being unorthodox. It has to break the existing paradigm,” she tells me. “It is a lot easier to find an unorthodox person than an unorthodox organisation. That is why innovation is so much more likely to be associated with an outsider prepared to fight for their ideas.”

Sinclair may not have been in the same league as any of the innovators in Schilling’s book. Nevertheless, he shared the same obsessive desire to think differently and make a difference. It may take an expert community to collect the tinder that enables innovations to catch fire. But sometimes it requires a singular individual to provide the spark.