Depop sale not a sign of deflating UK tech scene

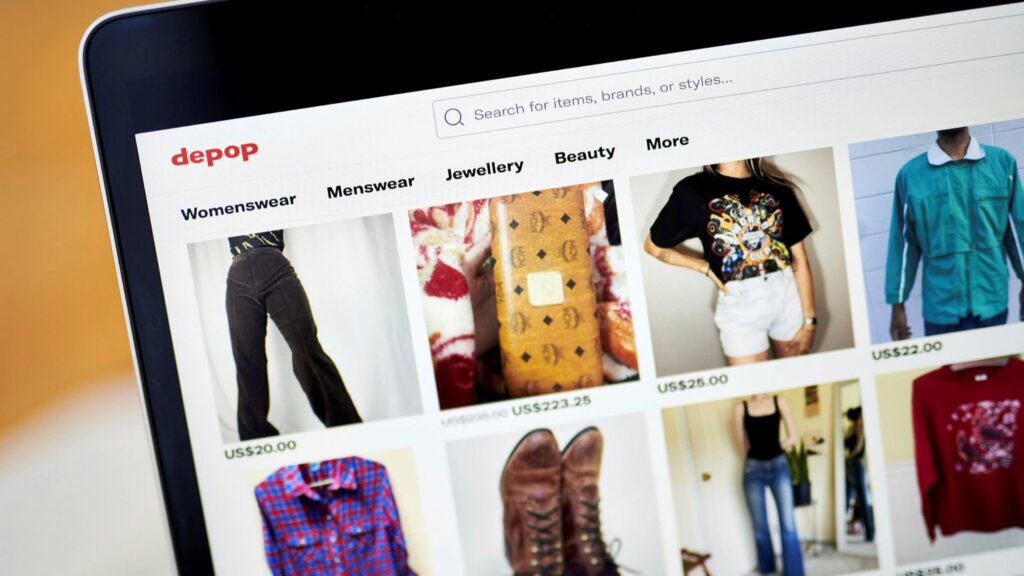

This month’s $1.6bn sale of Depop, a fashion app popular with “Generation Z”, has been an unlikely catalyst for a debate about the health of the UK’s tech economy.

Some have fulminated over the sale, claiming that UK tech champions are selling out too early and too often to foreign buyers.

“Why on earth is the government not using its new powers to screen takeovers,” Vince Cable, the UK’s former business secretary, told The Times, urging his successors in Westminster to have a “careful look”.

Depop is a bona fide phenomenon with environment- and fashion-savvy young people thanks to its blend of Instagram, eBay and charity-shop chic. It is a neat fit for New York-based Etsy, which is in need of younger users and can share expertise in operating an online marketplace for creative types.

But its sale does not quite raise the same strategic issues for the UK as the loss of a deep-tech innovator such as the UK chipmaker Arm, originally bought by SoftBank in 2016 but which is the target of a $40bn bid from Silicon Valley-based Nvidia. Given that Arm’s technology powers almost every smartphone and much more, it makes sense for regulators to examine Nvidia’s takeover bid.

The issues over Depop have more in common with those surrounding the sale of UK artificial intelligence pioneer Deepmind to Google in 2014 (when Cable, incidentally, was the UK’s business secretary). Has Depop sold too early?

That may or may not be the case but Depop and its sale is part of a more positive underlying trend in British tech. When the company was founded in 2011, a billion-dollar internet deal was something that most London tech founders and investors could only dream about. Industry meetings at 10 Downing Street were convened to discuss how to engineer this aspirational outcome for more start-ups.

In the decade since Depop was founded, the UK has produced more than 80 companies valued at more than $1bn, according to the Digital Economy Council and market tracker Dealroom. UK tech investment increased tenfold between 2010 and 2020, from £1.2bn to £11.3bn.

“People aren’t selling out. They are raising more money and getting bigger and bigger” while staying private for longer, says James Wise, partner at UK tech investor Balderton and an investor in Depop.

While buyouts of venture-backed companies in the UK total €7.1bn to date this year, according to Dealroom, investment into start-ups is greater at €12.4bn. That is already approaching 2020s total of €13.9bn in a year when €7.9bn worth of tech deals were made.

Even in areas of traditional weakness for the UK such as later-stage funding, there are signs of improvement. Just this week, Balderton announced a new $680m “growth” fund explicitly designed to help founders turn down premature takeover bids. “Many people are now building $5-10bn companies that would have had to sell historically,” says Wise.

Another nuance to the debate over whether the UK sells too soon is that taking the money from Silicon Valley need not always be a bad thing.

Venture capitalists say that it is often first-time founders who fold when a multimillion dollar offer is dangled in front of them. But many of these newbie entrepreneurs soon leave the big companies that buy them out to start again. The next time around, they have the experience and personal financial security not to sell so quickly.

“We’ve seen that cycle play out time and time again,” says Simon King, a partner at Octopus Ventures. Alex Chesterman is the UK’s poster child for this kind of thinking. He sold film rental site Lovefilm to Amazon for £200m in 2011; his property site Zoopla went public at a £1bn valuation in 2014; now he is in the process of taking his used car site Cazoo public at an $8.1bn price tag.

Cazoo has chosen to list in the US, via a special purpose acquisition company, rather than do an initial public offering in London. But despite listing in New York, Cazoo will keep its headquarters in the UK, where it employs almost 2,000 people. Etsy has also promised that Depop will remain operationally independent, keeping its London office and current management team.

Any threat to block the Depop deal is likely to trigger a fierce backlash from the UK’s tech investors, who would argue that the “right to be acquired” is of greater importance for the long-term health of British tech than the more traditional protectionist stance.

tim.bradshaw@ft.com